Student who collected garbage to pay for college is accepted to Harvard Law School

A Maryland college graduate has been admitted to Harvard Law after overcoming a laundry list of obstacles.

Until he turned 8 years old, Rehan Staton said his childhood in Bowie, Maryland, was a life of privilege -- loving parents, a supportive big brother and a cushy, private school education, including a tutor.

Everything changed when his mother left the country and his father lost a job, later having to work up to three at a time just to pay the bills. Food became scarce. Turning on the thermostat was a luxury they couldn't afford.

"I would have to sleep with a heavy jacket on when it was cold," Staton said. "I was always angry and hungry. It affected my academic work at school, and I started to perform horribly."

Staton went from straight As to near the bottom of his class. He said he couldn't concentrate at school and would sleep during class because it was warm there. Once he reached the seventh grade, a teacher told Staton he needed special education, which made him "absolutely hate school."

But it was clear a change was needed, so Staton's dad went down to a local community center and asked for help tutoring his son. An aerospace engineer offered to tutor Staton for the remainder of the school year, free of charge.

"I ended up making honor roll the rest of the year," Staton said. "He was like an uncle or godfather that gave me food and a place to stay sometimes. After we stopped the tutoring sessions, my grades suffered again."

Staton spent his high school years as a talented athlete, training religiously to become a professional boxer -- skills he became known for.

"I won a lot of martial arts competitions," Staton said. "From all my teachers, mentors and classmates -- no one ever asked me about school or college. It was always, 'How'd your tournament go? How's training? When's the next match?'"

Tragedy struck senior year when Staton suffered severe tendonitis in both shoulders not long before commencement. He couldn't lift either arm above his head for months. The injury wasn't career ending, but without medical insurance, Staton said physical therapy wasn't an option.

With dreams of going pro dashed, he scrambled to apply to colleges and was rejected by all of them. Staton's body slowly recovered from martial arts and he got a job as a trash collector at a local sanitation company. Many co-workers had been formerly incarcerated. As he made the rounds picking up garbage, crew mates couldn't help but ask a simple question: "What are you doing here?"

"They would say, 'You're smart,'" Staton said. "You're too young to be here. Go to college, and come back if it doesn't work out."

It was the first time someone outside his family, other than his seventh grade tutor, encouraged Staton's intellect.

"Teachers, church leaders, and other upper echelon people known for being a role model in society were the ones that never saw anything in me," Staton said. "It was the sanitation workers that lifted me up to make me even want to go to school."

WATCH: Despite homelessness, graduate becomes valedictorian

Several co-workers spoke to managers at the sanitation company, and they put Staton in touch with a professor at Bowie State University -- a school that denied him a few months earlier. The professor was impressed with their conversation and convinced the admissions board to reverse its decision.

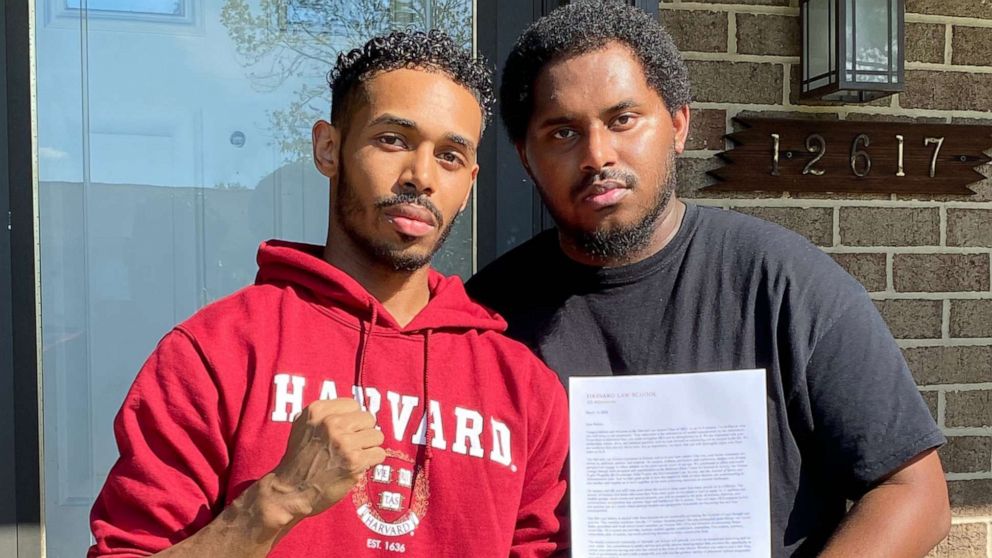

Going to college forced Staton's older brother, Reggie, to drop out. They both knew someone had to be working full time along with their dad or they'd lose the house, Staton said. It was a decision Reggie made on his own.

"My brother knew I'd be stuck if I didn't jump on this opportunity and go to school because of my grades," Staton said.

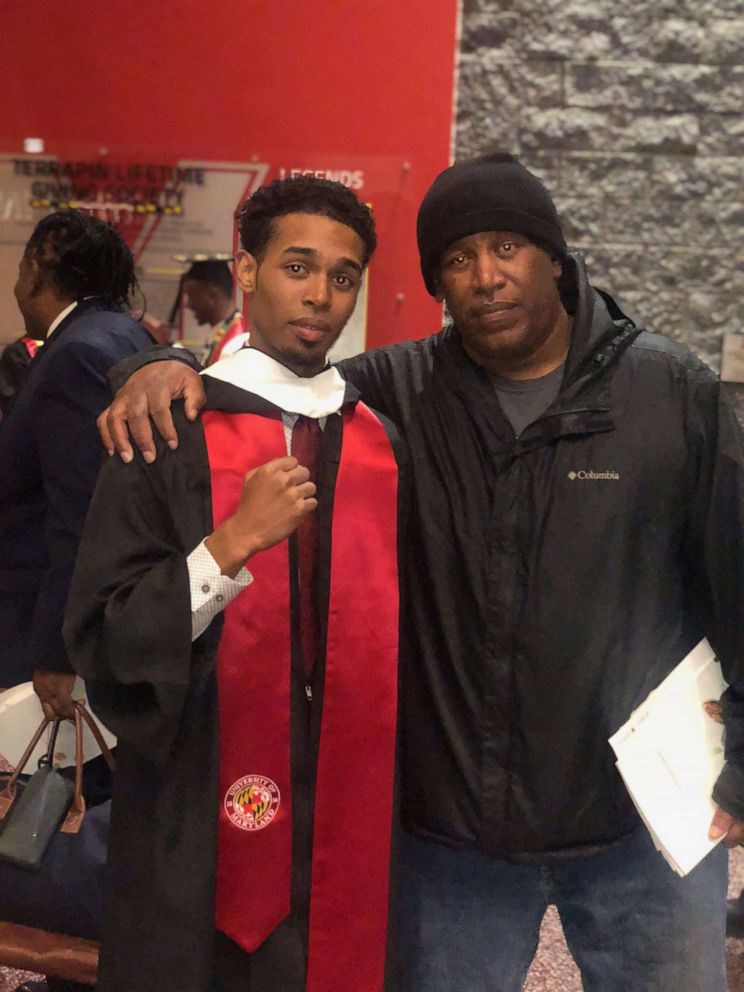

After receiving a 4.0, Staton matriculated to the University of Maryland, where he flourished as the president of the undergraduate history association, history representative for the dean's cabinet and ultimately the graduation speaker for the class of 2018. Through it all, he continued as a garbage collector, waking up every morning before sunrise as he worked two separate shifts between classes. You wouldn't find him at a party.

"I had to give up any sort of social life," Staton said "I just put my head down and stuck to a schedule to make it all happen."

Shortly after graduation, Staton's health began to deteriorate unexpectedly, but landed a job at a political consulting firm in Washington, D.C. He took the LSAT and applied to law schools while working full time. In March, Staton, 24, learned he'd been accepted into his top choices -- USC, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard.

"It was a surreal moment for me," Staton said. "It made me feel like my brother and my dad's sacrifices were not in vain. We did it."

Staton is now set to enroll at Harvard Law School this fall. For anyone looking for inspiration during difficult times, Staton said to "love yourself enough to get what you want out of life. You can always see the light in any dark situation, and you need to hold on to that light."