Ron Ehrenberg was ready to give up.

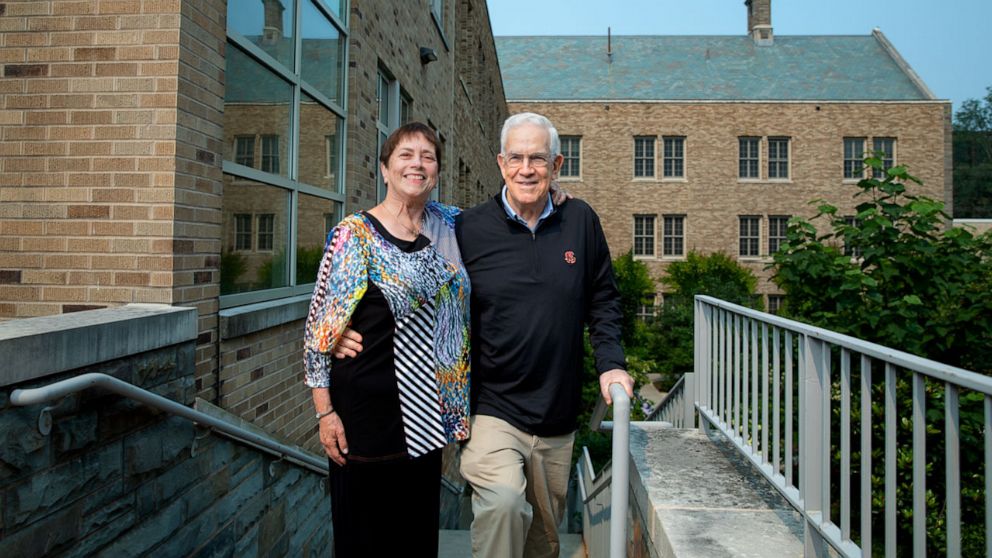

The professor at the Industrial and Labor Relations and Economics School at Cornell University had been looking for a kidney transplant for two years, testing every friend and family in hopes of finding a potential donor.

With no one meeting the requirements, Ehrenberg, who was living with end-stage renal disease, began dialysis to give him more time with his family. As a result, his life was tethered to the hospital because a dialysis machine and supplies would fill up his entire car for a two-day supply. He was also not allowed to travel during a five-year period because if a call came in saying that a kidney was available, he would have to go to the hospital almost immediately.

“I was so fatigued and had so little energy,” said Ehrenberg. “We were so worried.”

Ehrenberg resigned himself to waiting for a kidney from a deceased donor, knowing that those kidneys tend to wear out sooner and are more rare.

A kidney from a live donor can start functioning immediately rather than taking a few days to kick in as with a deceased donor, according to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. What's more, relatives' kidneys tend to have less risk of rejection and a potential donor can be tested ahead of time, making the process more convenient, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

Along with finding a donor, Ehrenberg, 75, worried about contracting a disease from an unknown deceased donor and not being healthy enough for a transplant, along with any complications from cancer to heart conditions that could disqualify him from being a recipient.

Finding a hero and finding hope

Five years after being placed on the transplant list, Ehrenberg got a call from the nurse that a live donor had come forward. The donor asked to remain anonymous, but Ehrenberg begged the hospital to tell the donor he wanted to know who they were.

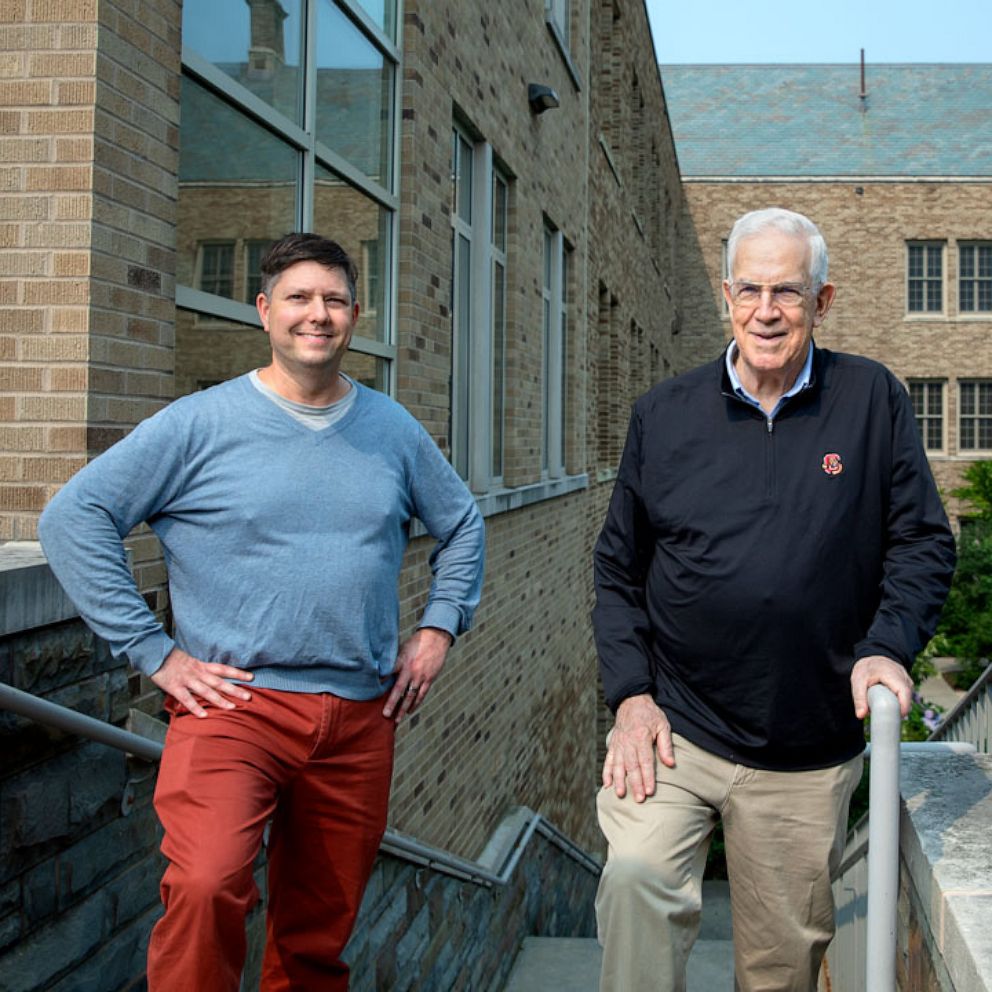

The nurse passed along Ehrenberg’s request. That’s when his co-worker of seven years, Adam Seth Litwin, an associate professor at the school, sent an email revealing his life-saving gift.

Litwin said he got serious about donating after his mother-in-law died.

“She and I were very close and she was actually the same exact age as Ron,” explained Litwin. “She was not a candidate for a transplant, but it brought home to me how little time she was able to spend with her grandchildren, my children, and that there is something I could do for someone else that would kind of prevent that from happening again.”

“I'm kind of grumpy and curmudgeon on the outside, so this is definitely not consistent with whatever images that I have created to those around me,” he added.

Initially, Litwin was not allowed to donate his kidney, but he spent two years secretly improving his health. He improved his diet, stabilized his blood sugar and lost around 25 pounds. He kept it off for a year and got approved to donate on April 20, which happens to be Ehrenberg’s birthday.

Ehrenberg said that Litwin initially wanted to remain an anonymous donor, but Ehrenberg convinced his friend to come forward to help potentially save more lives. Litwin said that he donated his kidney not just to give more years to his friend, but also to teach a lesson of love to his two children.

“I keep joking that I don't want people to think just because I did this that I'm not still a miserable b------," said Litwin.

While Litwin may not think of himself as a particularly generous person, Ehrenberg disagreed.

“Adam was the real hero,” said Ehrenberg. “I am deeply indebted to Adam and I will spend the rest of my life trying to think about how I can repay him.”

“We hope we could encourage more people to be donors either alive or deceased kidney donors,” said Ehrenberg.

Ehrenberg said he plans to spend his new retirement making up for years lost to illness. Litwin plans to spend more time with his family. Both are excited to see Ehrenberg spend many more years with his grandchildren.