Olympic hopeful trades sneakers for Army fatigues, all in the name of country and giving back

Sam Chelanga did not want to be a runner; it just happens to be his life story.

"When I'm running, I feel relaxed and I feel appreciative of where I've gone so far and it's a way for me to remind myself to not forget how far I have come," he said.

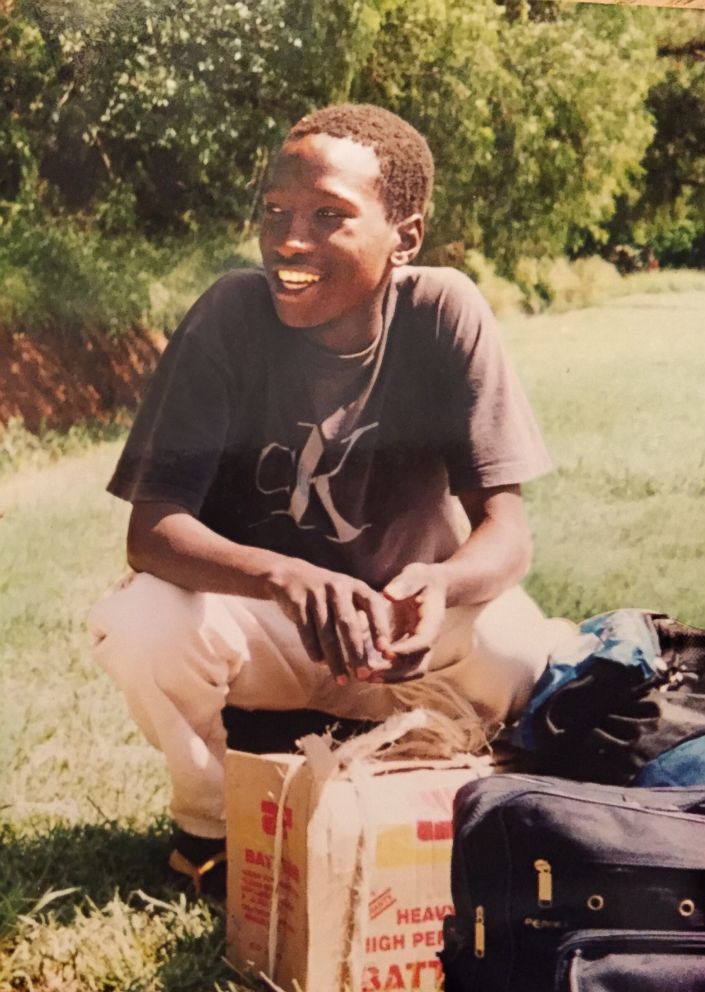

Sam Chelanga said that life was tough and that he wanted to get out of his poor, rural village in Kenya.

His mother passed away when he was young and then his father fell ill. One of 12 children, Sam Chelanga said he had to look for ways to survive. Opportunity was scarce and he wanted to go to college.

"I thought maybe I could get like a law degree and then go back and help my family," he said.

But, college seemed out of reach. Then, he met a friend through his brother who told him about running and getting a scholarship in the U.S.

Sam Chelanga's older brother Josh Chelanga was a marathoner. His friend was professional Kenyan runner Paul Tergat. Tergat saw something special in Sam Chelanga and offered him the chance of a lifetime.

"I looked at him and I said, 'I don't think I can run. I've never run. And, I'm not even good,'" Sam Chelanga said.

He didn't want to follow in his brother's footsteps. He didn't enjoy running. Yet, Tergat persuaded him to come to Nairobi for a camp with world-class runners.

So, off Sam Chelanga went to the running camp, where he trained for about a year and a half. He won a scholarship and a one-way plane ticket to the U.S. He boarded the plane determined, he said, to use his good fortune to help his community.

For a year, he attended and ran track for Fairleigh Dickinson, a private and nonsectarian university in Teaneck, New Jersey.

"I did very well," Sam Chelanga said, "(but) I just wasn't true to myself because I never went to church. I wanted to go to Christian school."

In the fall of 2007, he transferred to Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia; however, because he'd left Fairleigh Dickinson before his scholarship allowed -- to the university's distaste -- he had to sit out a year at Liberty before he could run on its team.

"It was the first decision I ever made by myself in my life and the best one," he said. "My life took off at Liberty. ... I started getting better in running. That's when I started winning like NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) nationals."

At Liberty, he quickly became a legend, holding the NCAA record in the 10,000 meter. He won several national titles and was responsible for Liberty's winning four of its six national titles in its history of track and field.

"I definitely felt like he had a chance to be an Olympian someday," said Liberty coach Brant Tolsma.

Sam Chelanga said he wanted to race in the Olympics for the U.S. but learned that he'd need a green card, making him a permanent resident. He started the process for U.S. citizenship but, before he could get a green card, he found love with college sweetheart Marybeth Carlson, a member of his cross-country team. The two eventually married.

Marybeth Chelanga said she'd grown up in love with Africa, plastering her walls with maps and pictures of people in remote villages.

"She was really nice and she wanted to know about my village," Sam Chelanga said.

Marybeth Chelanga helped him stay the course with running and giving back.

In 2011, he graduated from Liberty and soon afterward was offered a contract and salary from Nike. The company paid for his travel and training.

"Everybody in the track and field world realizes that Sam signing with Nike was, was a big deal," said Liberty coach Clendon Henderson.

"There (were) moments that I looked at myself and I said, 'There must be a reason why I'm being blessed like this,'" Sam Chelanga said.

Sam Chelanga said that every Christmas, he'd pick 10 struggling families to sponsor but felt inspired and motivated to do more. Marybeth Chelanga said that people in his village were getting sick, specifically from typhoid because of the water, so they started brainstorming ways to help.

"We wanted to drill a well. ... It's a lotta money," Sam Chelanga said.

So instead, with the help of Marybeth Chelanga's father, he came up with different plan: water filters.

"It's like a giant Brita filter and it works," Sam Chelanga said.

"Each one serves three to four families. And, right now, we have about 100 filters," Marybeth Chelanga said. "We've heard reports that typhoid is no longer in their community."

Marybeth Chelanga said becoming a U.S. citizen was always in view for her husband.

"I knew how hard I worked in Kenya and how hard I worked here," he said. "It's not that I was special or anything. It's just the U.S. system worked really well to nurture my talents. ... That's why I wanted to become a part of it."

In 2015, Sam Chelanga crossed a different type of finish line: He was approved to become a U.S. citizen. When the Olympic trials came along, he ran and finished sixth in the 10,000 meter.

But an Olympic uniform wasn't the only uniform that Sam Chelanga had in mind.

"I said, 'You know, I wanna go to the Olympics but if I didn't do the running, I would go to the Army. I really wanna go to the Army,'" Sam Chelanga said that he'd told his wife. "And she was like, 'Wow. Really?' I say, 'I do.'"

Marybeth Chelanga said the two planned for him to run two more races before he joined the Army.

"It literally all happened this summer," she said. "Now, he's in basic training."

After seven years at Nike and at the height of his career -- and some of his best years still ahead of him -- Sam Chelanga reported to Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina.

He was met with a lot of blank stares, he said.

"People thought it was crazy," he said.

"What he's giving up is, you know, a lotta fame and glory and money and success and comfort. And to give up all of that is pretty hard to understand," Henderson said.

Sam Chelanga said Nike had even offered to renew his contract and a friend had offered him a job.

"I just really wanted to do this (join the Army)," he said.

So at the age of 33 -- more than a decade older than the average trainee -- Sam Chelanga started basic training at Fort Jackson.

"Age is just a number. If you wanna do something, (you) just have to do it. I don't even think about (it) every day. I don't even know how young those guys (are). ... Nothing really with basic training comes easy," he said. "It's just like running. It's not supposed to be fun."

Sam Chelanga said the only hard part was missing his family.

Marybeth Chelanga, who moved in with her parents temporarily for extra support in Georgia, said their oldest son misses Sam Chelanga a lot. She is now expecting their third son.

"I think, in the long run, that's the whole point of sacrifice," she said. "I'm willing to miss him, even though it's super painful. ... My parents are super helpful. It's nice having grandparents around."

The family will be reuniting soon after Sam Chelanga completes basic training. He will begin officer school in Georgia in October.

Sam Chelanga said without the U.S., he would not be where he is today. And as thankful as he is to be an American, he said he still cherishes his homeland. He hopes to serve both countries as well as he can.

"The reason Sam wanted to go to a university, or then become a runner, was always to help his family," his wife said. "So the more he's (been) given, the more he tries to find ways to give to others."