Hard choices face teacher and some parents as school district struggles with asbestos

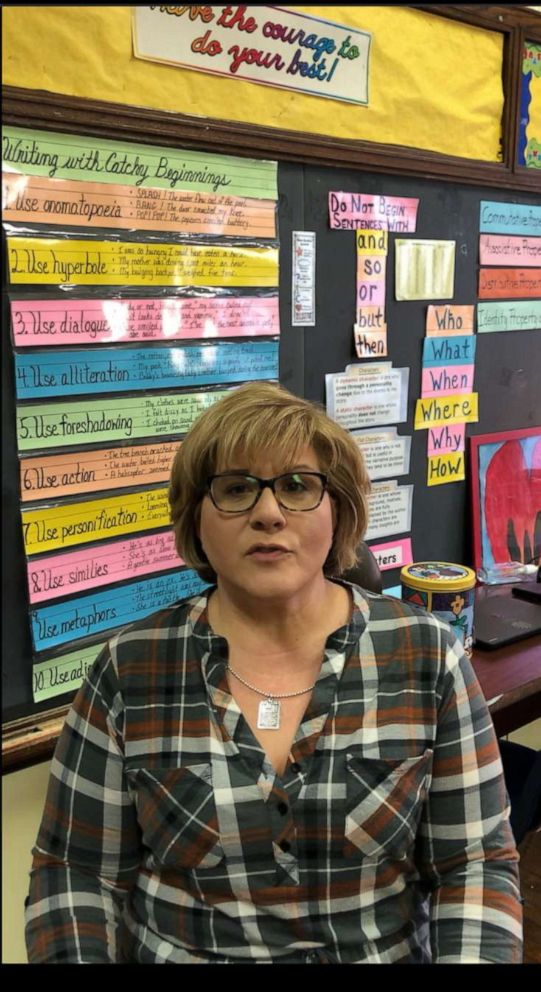

She's touched countless lives after 30 years as a Philadelphia public school teacher.

But in August, 51-year-old Lea DiRusso was forced to give up her cherished career after she says she was diagnosed with mesothelioma.

"I didn't know it was my last year," DiRusso told "GMA." "I just feel like I didn't get to end it the way I wanted to end it."

The aggressive and deadly cancer of the lungs and abdomen is almost always caused by long-term exposure to asbestos, according to agencies such as the Mayo Clinic, American Cancer Society and the World Health Organization.

"I planned on spending my golden years with someone that I just married a few years ago and that doesn't look like that's gonna happen," DiRusso said. "I feel like I have tomorrow. That's about it."

A threat exposed

Philadelphia schools have a known asbestos problem, with the teachers union's Health and Welfare Fund describing some schools as having crumbling, potentially harmful conditions.

"We're not talking about some obscure part of the school, like the boiler room," said Wendy Ruderman, a lead reporter at the Philadelphia Inquirer, whose 2018 Pulitzer-nominated investigation revealed dangerous asbestos conditions in seven out of 11 tested schools. "We're talking about highly trafficked areas where kids are running around," she added, noting that "conditions are just horrific." The school district has since clean contaminated areas of the seven schools.

Asbestos was once considered a miracle material that was widely used for insulation and soundproofing, with experts saying that when it's covered and undisturbed, it's not dangerous. But years of wear and tear can cause the substance to become airborne, and breathing and ingesting it could lead to a host of cancers. Government agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency, say there is no safe level of asbestos exposure.

The schools where DiRusso spent her 30 years teaching have each had documented asbestos problems.

"If she was exposed to elevated levels of asbestos ... in the two buildings in which she taught, it would be a causative factor in her developing her mesothelioma," said Arthur L. Franke, a professor at Drexel University focused on environmental and occupational health.

"I was completely unaware, as are my colleagues and staff and students, that there even was asbestos present in the school building," DiRusso said. "I did not know that the steam pipes behind me were wrapped in asbestos. And I touched them and I hung clotheslines to hang student work. And I used it because I was creating a home for my students."

DiRusso says she knows of no other place she was exposed.

"I'm often seeing damaged, exposed and available asbestos that are in areas where there are children and staff," said Jerry Roseman, an environmental scientist who was called in by both the school district and teachers union's Health and Welfare Fund regarding asbestos complaints. "I have a kind of searing image in my mind of a child who has his arm around an asbestos-covered pipe in a gym and he's sucking his thumb. That's a problem."

Roseman said he sees exposed asbestos that's been present for months, even years.

"The only good news is that in these situations for people not in direct contact, the level of risk is small," he said.

The choice to be safe

Some worried public school parents have faced tough decisions.

Charmaine Mitchell pulled her son, Allen, out of a local elementary school in early November.

"My frustration came in when I realized, all this time, Allen has white stuff on his pants," she said.

Josh Meyer, another parent, said, "We have enough trouble getting great teachers into our schools, keeping them in our schools, without them putting their lives at risk."

"I feel confident that my kids are going to a safe school, but we should all be able to say that and the fact that we can't all say that is a problem," said parent Stacy Koiler.

"It's like 'Dante's Inferno' or somethin'. Like, every day, you're making this horrible decision over and over," said David Masur, who runs the Philadelphia Healthy Schools Initiative, a coalition made up of parents, council members, teachers and environmental advocates to make Philadelphia district schools safer and healthier for children.

"This is a systemic problem. It's system-wide. It's district-wide. And it's frustrating. I mean, as a parent, certainly, I think we have a right to information. We shouldn't have to request it. It should be available for us to see and read and review all the time."

The Philadelphia school district told "GMA" it realizes that it has a serious challenge with asbestos in its more than 200 school buildings. It says its goal is to "have the best notification system possible, to have the most effective response possible and to eventually remove as much asbestos from our schools as possible," announcing a new cleanup project as recently as this week.

"I trust that when my kid goes to school, he's gonna be safe," said parent Gilberto Gonzalez.

But that cleanup may have come too late for DiRusso, who vowed to fight both for her life and the schools.

When asked if she would return to teaching in a Philadelphia school if given the opportunity, DiRusso said she wasn't sure.

"I don't know if I would feel comfortable knowing that I'm going to a place where someone didn't tell me that there was a toxic substance and that it was in my midst -- 2 feet from my head, every day, all day."