When this artist honored Princeton’s blue-collar workers, the university took notice

As he watched his mother create masterpieces on a blank canvas in their Detroit home, 4-year-old Mario Moore had the thought, "I want to be an artist." With a crayon and sketchbook in hand, he, too, would draw.

Today, almost 30 years later, Moore has followed his childhood passion to become a painter and is using his artistic abilities to change the narrative of African American blue-collar workers.

Moore was using his small Brooklyn bedroom as an art studio when he received the news that he was awarded The Hodder Fellowship at Princeton University for the 2018-2019 academic year. The now-32-year-old packed his bags, moved to Princeton, New Jersey, and decided to use this opportunity to help change the portrayal of black labor workers by bringing them to the forefront of his paintings.

"To me, people who cook in the cafeteria or clean the campus are just as important as deans or past presidents," Moore told "Good Morning America."

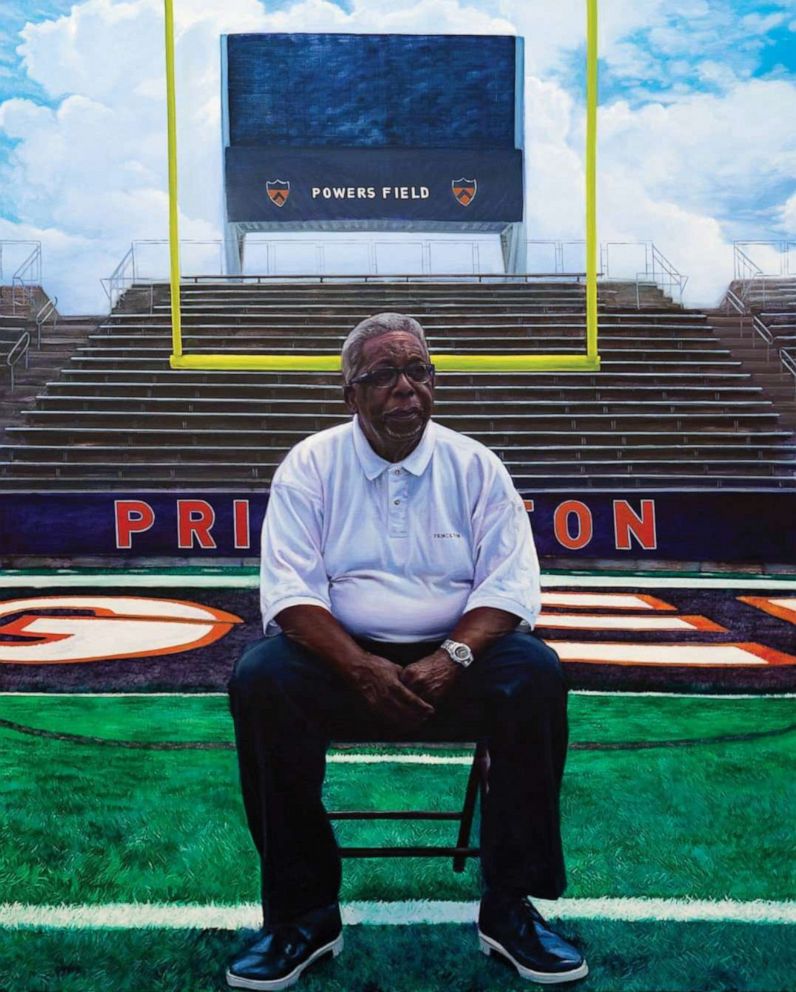

He made it his mission to seek out 10 campus workers, all strangers, and paint their portraits while learning about them over several conversations.

"I told them about my life, they told me about theirs," he said. "I drew them during our conversations."

Moore viewed blue-collar jobs as being a ground base for African Americans during The Great Migration. He recalled being a student and interacting with these types of workers day-to-day. Moore felt the comfort of always being able to talk or joke around with them, which eventually ended up positively impacting his undergrad years.

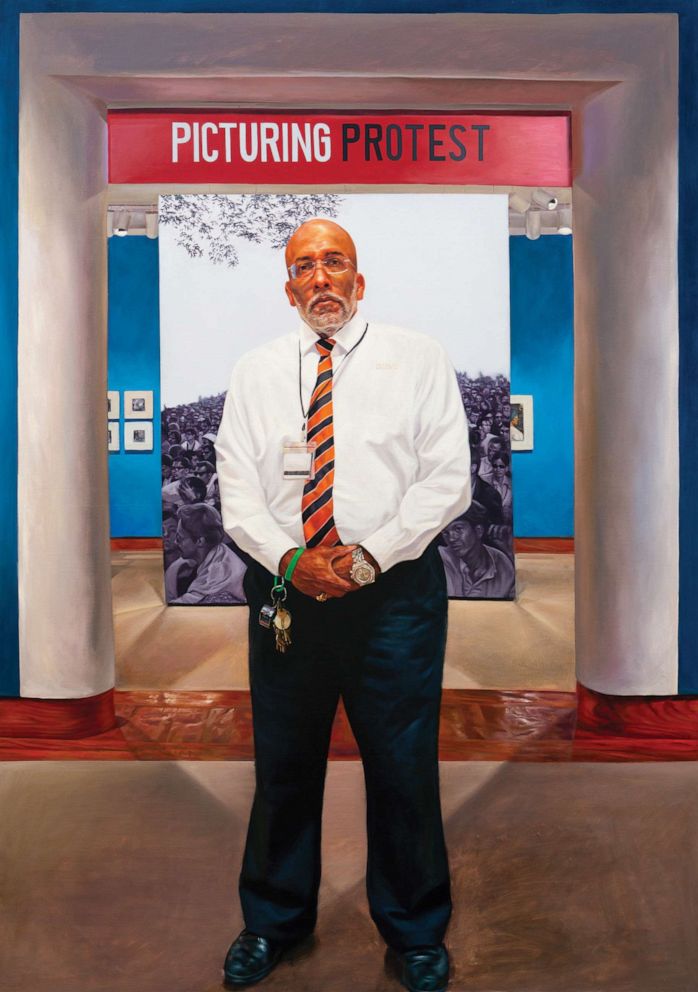

Moore met with various types of people around Princeton’s campus, from food service workers and custodians to athletic department groundsmen and more. While strolling through the Princeton Art Museum, he also met Guy Packwood, a security guard who has been working at the university since 2013.

"He walked up to me and struck up a conversation," Packwood said. "We talked about my past career as a state trooper and my involvement in starting New Jersey’s chapter of The National Black State Troopers Coalition. He was genuinely interested in getting to know who I was."

Moore formed a friendship with each of his subjects, planned one-on-one lunch meet-ups and allowed them to watch him paint the portrait along the way.

By the end of his fellowship, Moore’s exhibit, "The Work of Several Lifetimes," was lined with 10 detailed oil paintings and 10 etchings of blue-collar campus workers.

"It starts a bigger conversation about who deserves to be recognized," Moore said.

Five of these paintings have now been purchased by the university and will be permanently displayed around campus. One piece is already on full display at the Princeton University Art Museum.

Future generations of students will now see more representation on walls around the university. For Sann Sanneh, who graduated from Princeton last spring, that means the world.

"The student body could name at least one or two people from Mario’s paintings because they are literally the backbone of our university."

"When you see the subject in a painting, you immediately think it’s someone important," Sanneh told "GMA." "While I was at Princeton, most of the portraits I saw were of older white men and I could not tell you the name of a single one of them. It made me feel belittled."

Before graduating, Sanneh produced a senior thesis photo exhibition focused on black subjects. He often worked down the hall from Moore and understands the importance of showcasing individuals who play a major part in keeping the school running.

"I’d be willing to bet that a vast majority of the student body could name at least one or two people from Mario’s paintings because they are literally the backbone of our university," he said.

The hard work of blue-collar workers, especially those who are African American, is often overlooked. Through his efforts, Moore hopes to highlight the importance of representation and start a greater conversation about who deserves to be recognized.

"Most universities and institutions are grounded upon blue-collar workers. Now students who walk around these halls will be able to see something a little more contemporary and present," he said. "It starts a bigger conversation."