Woman works to end Black maternal health crisis after daughter dies after giving birth

When Wanda Irving looks into the eyes of her 5-year-old granddaughter, Soleil, she said she instantly sees her daughter, Shalon Irving, whose death shortly after giving birth to Soleil has since shaped the trajectory of their lives.

"She’s got her mom’s eyes and her mom’s smile and her mom’s fearlessness and her mom’s persistence," Wanda Irving told "Good Morning America" of her granddaughter, whom the family calls Sunny, after her middle name, Sunshine. "She has her mom’s memory, because her mom wouldn’t forget anything."

After Shalon's death in January 2017, three weeks after giving birth, Irving uprooted her life to move to the Atlanta area, where Shalon worked as an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service.

Irving has cared for Soleil full-time ever since, working to make sure her granddaughter knows all she can about her mom, whose ultimate dream was motherhood.

"[Shalon's] pictures stay up. Everything is around that her mom would have liked," said Irving, who said Soleil loves to cook because she knows her mom did, too. "I try to tell her every single day what a great mom she had, and she can tell you stories about her mom because of what she's heard. She asks me repeatedly to tell her mommy’s story again."

In addition to keeping her daughter's memory alive, Irving has devoted her life to ending the maternal mortality crisis among Black women in the United States so that other families don't face grief like hers.

I have to face my granddaughter every single day

"I have to face my granddaughter every single day, and she's still asking where's her mother and why isn't her mother here," said Irving, the co-founder of a maternal mortality-focused nonprofit organization called Dr. Shalon's Maternal Action Project.

"That doesn't make sense to me, why she has to go through that kind of pain," said Irving. "So we can't let this continue to happen."

According to the CDC, around 700 women die each year due to complications within the first year after giving birth in the U.S., which continues to have the highest maternal mortality rate among developed nations.

As a Black woman, Shalon faced disproportionate odds when giving birth to her first child. Black women in the U.S. die of maternal causes at nearly three times the rate of white women, according to CDC data released in February.

A heartbreaking death and a newborn

As a doctor, Shalon was prepared for the birth of Soleil, according to her best friend, Bianca Pryor, who met Shalon in 2002 as a fellow graduate student at Purdue University and, by chance, became pregnant with her first child at the same time as Shalon.

"She knew her body in and out. She had a Ph.D., but one would have thought she had an M.D. She was brilliant," Pryor said. "She had researched everything about pregnancy and delivery, and she was so prepared."

Shalon gave birth successfully to Soleil via C-section on Jan. 3, 2017, with her mom by her side, and then was discharged from the hospital four days later after a routine stay, according to Irving.

After a few days at home, according to Irving, Shalon began experiencing complications including a hematoma, blood that collects and pools under the skin, as well as rising blood pressure, swollen limbs and a C-section wound that was not healing. Irving said she believes doctors “dismissed” diagnosing Shalon with postpartum preeclampsia, very high blood pressure that can occur 48 hours to 6 weeks after giving birth, because she did not meet all the diagnostic criteria.

"I think she probably went to the doctor at least nine or 10 times in those two weeks," Irving said. "I know that last week she went almost every single day, and every time she was sent back home."

She kept saying that something wasn’t right

Pryor, who lives in New York and had just given birth to her own son in an emergency C-section at 23 weeks, said she remembers getting updates from Shalon about her complications.

"She pushed back on the medical care teams," Pryor said. "She kept saying that something wasn’t right."

And then on Jan. 24, Pryor said a missed phone call led to a text from Irving with the message, "B., Shalon stopped breathing."

At home in Atlanta, Shalon, then 36, had suffered a cardiac arrest and collapsed. She was taken by ambulance to a local hospital, where she was put in the intensive care unit, according to Irving.

For several days, her family and friends stood vigil by her bedside, according to Pryor, who flew in from New York.

When we put Soleil on top of her, one tear ran out of Shalon’s eye

"We stood by her side. We prayed," Pryor said. "The hardest was when we decided that we would bring Soleil in so that Shalon could hold her one last time. I'll never get that image out of my head."

"I remember when we put Soleil on top of her, one tear ran out of Shalon’s eye, and we just held space. We stayed in that moment," she said.

On Jan. 28, two days after learning Shalon was brain dead, Irving said she had to make the decision to remove the respiratory machine that had been keeping her daughter alive.

"We took a look at her medical directive and one of the things that we saw was that in the directive, she had handwritten, 'Mommy, I will try hard if anything happens, but if there's no hope, let me go. Just let me go,'" Irving said. "I didn't want to let go, but I wanted to honor her request."

Picking up the pieces to create change

Immediately after Shalon's death, Pryor said she spoke to Irving about the dreams she and her best friend had shared for their children, like how they wanted to raise their kids and the people they hoped they would become.

As the months and years went on, Pryor and Irving also spoke about the dreams Shalon had for her career and the legacy she would want to leave behind.

"We started dreaming together, Wanda and I, picking up where Shalon and I left off, and putting our pain into purpose," Pryor said.

Together, in late 2019, Irving and Pryor founded Dr. Shalon's Maternal Action Project to make giving birth in the U.S. an equitable right for all.

"Shalon was such a fierce equity warrior," Irving said. "She had her motto, 'I see an equity wherever it exists. I'm not afraid to call it by name, and I fight hard to eliminate it. I vow to create a better Earth,' and that was Shalon in a nutshell."

After Shalon's death, Irving said an autopsy report listed her cause of death as cardiac arrest caused by high blood pressure. Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a condition that, according to the CDC, contributes to a "significantly higher proportion of pregnancy-related deaths" among Black women than among white women.

Both Irving and Pryor said they felt that after Shalon gave birth, her health complications were not taken seriously enough by her medical team.

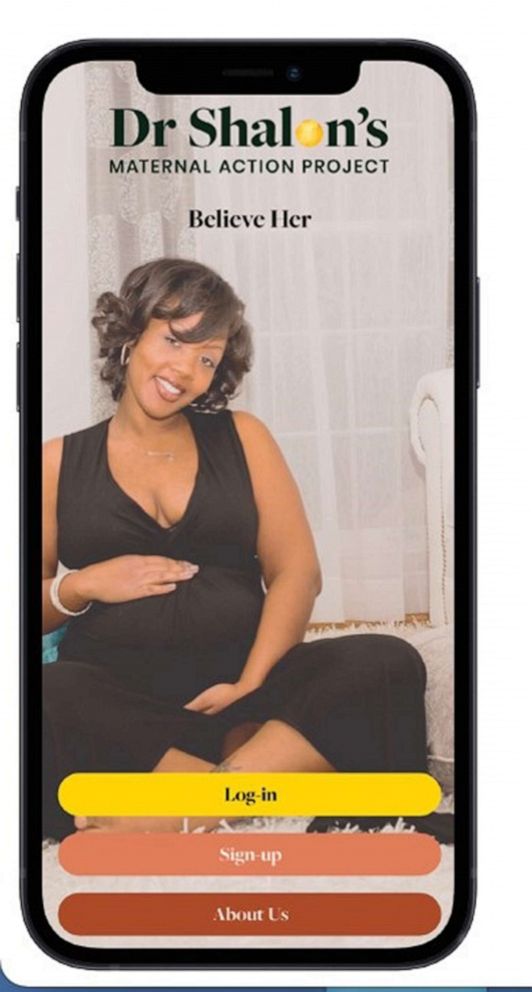

As a result, they created Believe Her, an app that provides maternal health resources for Black women and gives them a space to share their experiences.

"Our mission is to create that collective line of defense, so for all the Black mothers and birthing people out there to learn, what is the language, how do you push back when someone says, 'Oh no, you're fine,'" Pryor said. "That is our response back, believe her."

Empowering Black women against the odds

On Wednesday, during Black Maternal Health Week, the Biden administration announced an additional $16 million in funding for programs to strengthen programs that aim to address disparities in maternal and child health, including a state-level program to "deliver high-quality maternity care services, provide training for maternal care clinicians, and enhance the quality of state-level maternal health data."

On the ground, Believe Her is one of several apps created by Black women to help birthing Black women beat the odds stacked against them because of their race.

Black women are more likely than white, Asian or Latina women to die from pregnancy-related complications regardless of their education level or their income, data shows.

Why exactly Black women die at a higher rate than any other race during childbirth is the result of a web of factors, experts say.

Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as the death of a woman during pregnancy or within a year of the end of pregnancy from pregnancy complications, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiological effects of pregnancy, according to the CDC.

One reason for the disparity is that more Black women of childbearing age have chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and diabetes, which increases the risk of pregnancy-related complications like preeclampsia and possibly the need for emergency C-sections, according to the CDC.

But there are socioeconomic circumstances and structural inequities that put Black women at greater risk for those chronic conditions, data shows. And Black women often have inadequate access to care throughout pregnancy which can further complicate their conditions, according to a 2013 study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Anecdotal reports show that the concerns of Black women experiencing negative symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum are specifically ignored by some physicians until the woman's conditions significantly worsen, at which point it may be too late to prevent a deadlier outcome.

One app on the market, IRTH, provides a platform for Black women to share reviews of care providers. The app's founder, Kimberly Seals Allers, said she was inspired to create a tool for other Black women after feeling her "wishes were ignored" when she gave birth in a New York hospital.

Maya Hardigan, a mom of three in New York, said she created another digital health platform, Mae, for Black women in part because of her own experience giving birth to her first child via C-section.

I did everything I knew to plan

"I did everything I knew to plan," Hardigan said of her first pregnancy. "I took a birth education class with my husband. I had a birth plan. I rotated through all the doctors in our OB practice to make sure I knew everyone and I talked to each of them about the birth experience I was seeking."

Hardigan said she ended up giving birth in a C-section that, though it ended successfully for both her and her daughter, was a scary experience.

"I felt that I just didn't have a choice, number one," Hardigan said. "And number two, I felt very confused, because it is such a vulnerable moment."

The Mae platform connects Black women with local support networks and with doulas, who can be a birthing mother's advocate in the delivery room and provide pre- and post-natal care. It also allows women to create their own birth plans and to track and monitor their conditions during and after pregnancy, according to Hardigan, who left a 20-year career in the health care industry to launch Mae.

According to Pryor, the different apps are all working toward the same goal of empowering Black women with the tools and support they need to successfully give birth.

"I really do believe we're pioneering the way ... to solve for this," Pryor said of the Black birthing crisis.

For Irving, she said she dreams that when her granddaughter grows up, she will not only not see an end to the crisis, but know that her mom played a critical role.

"I hope that [Soleil] will understand and appreciate as she grows up that [her] mom was an important person in this fight, and because of her and her life and what she did, things have changed," said Irving. "That's what I want her to be able to say."