Running a food truck is way harder than it looks

With the warm weather, food trucks -- like daffodils -- are literally springing up all over. And not just the taco trucks of old.

A new generation of gourmet food trucks is bringing ethnic cuisines and exotic tastes to young urban dwellers, revitalizing neighborhoods and changing the way America eats. It's the fastest-growing category in the foodservice industry, according to an Intuit report, reaching a record $2.7 billion in forecasted revenue in 2017.

But it’s not as easy as it looks.

“We see these trucks selling fun food from all over the world and think, 'How hard could it be? It’s just two or three guys or gals in a truck,'" Carolyn Cawley, president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation said. "But it's a lot harder than that. There are regulatory burdens and high costs for these entrepreneurs."

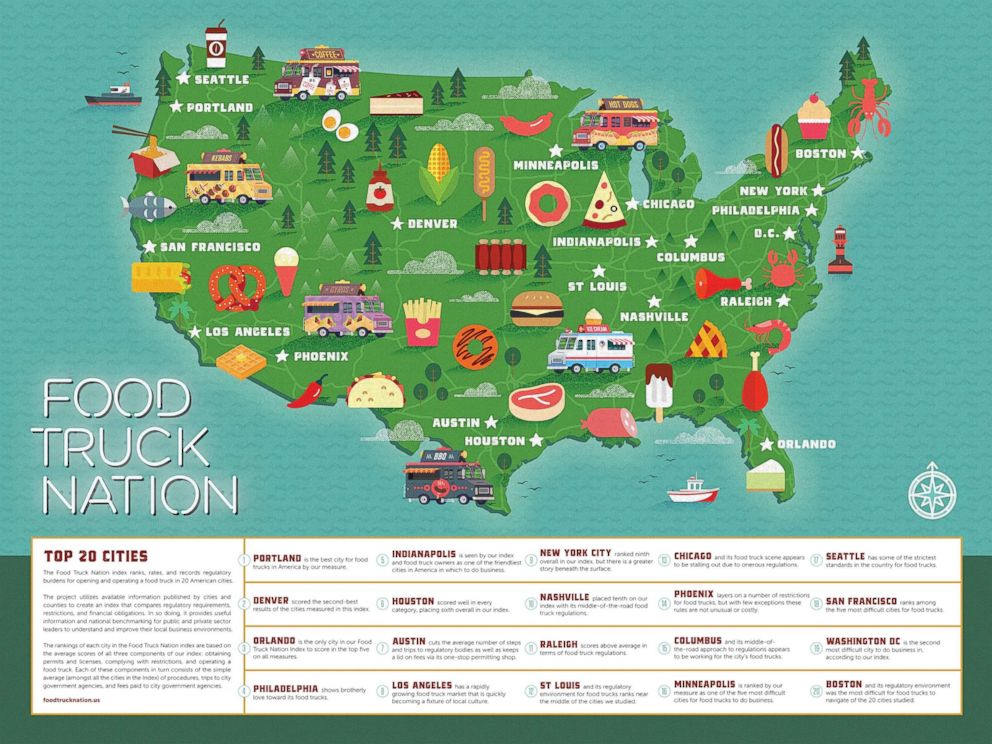

Cawley's organization released a new 12-month study called Food Truck Nation, which looks at the 20 cities across the country that have the highest concentration of food trucks, and ranks them according to how easy or hard it is to own a food truck in that city. The results were surprising.

“What we heard loud and clear from food truck owners in every city is they are encountering contradictory and often onerous regulations,” Cawley told ABC News. "The regulations that are impacting food trucks also end up hurting the consumer with less choices and higher costs."

5 most difficult cities to own a food truck

According to the study, the five most difficult cities to own a food truck are Boston; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; Minneapolis and Seattle.

The five friendliest cities are Portland, Oregon, Denver, Orlando, Philadelphia and Indianapolis.

“We found in Washington, D.C., that food truck owners need to make 23 separate trips to local agencies to get a permit,” Cawley said. “In Denver, it’s just an eight-step process, and in parts of Los Angeles, such as West Hollywood, food trucks are required to move to a different street every hour.”

In New York City, which ranked ninth in the study, Eden Gebre-Egziabher owns Makina Café, the first Ethiopian-Eritrean food truck in New York City. Gebre-Egziabher, who has an MBA in marketing, cooks up distinctive, exotic meals based on recipes passed down over generations -- from specialty chicken to beef sambusas to vegetarian dishes marinated in homemade spices -- but says regulations impede her day-to-day workflow.

"New York City rules and regulations are definitely not in favor of food trucks,” Gebre-Egziabher told ABC News. “By law you are not allowed to vend where there’s metered parking. Automatically that eliminates most of the streets in NYC. Whenever food trucks park on the street we get a ticket -- every day we get a ticket. They are anywhere from $65 and then it goes up. My record was four tickets in one day.”

15 year wait-list for a license

Another hurdle: obtaining a license.

“They have a 15-year waiting list to get a permit in New York City,” Gebre-Egziabher said. “The people who have licenses in the past lease them out to others who are coming in. It's such a big commodity right now that these permits going from $25,000 to $30,000 -- not to own but just to lease. The city could give them out for about $250 each, but they haven’t done that and they haven’t said why."

It's a very different story in Philadelphia, which ranked fourth friendliest city in the study. Here, Robin Adema, who runs the popular Foolish Waffles food truck, said licenses are affordable, ranging from $150 to $350. It's finding a place to park that’s hard.

“The biggest issue is where we are allowed to vend,” she told ABC News. “It’s pretty limited in the city center and most of the financial district. Also in areas like University City where there are lots of students and there’s a waiting list to get into those spots."

Fried chicken waffles and 'wagels'

Adema, who left her corporate job as a legal administrator four years ago to follow her passion, has built a loyal following with sweet and savory traditional Brussels and Liege waffles. She creates dishes like “wagels," similar to a bagel but with waffle dough, the pork belly banh-mi sandwich, the fried chicken waffle with bourbon pickled jalapenos, and the so-called ”sweet and salty” sugar waffle topped with black pepper bacon toffee, housemade salted caramel, whipped cream and smoked sea salt.

Another challenge: festivals and other events take 35 percent of their profit off the top.

“If we go to a venue and they charge us, they end up taking a third of our profit. That’s a lot when we don’t make that much money,” Robin told ABC News. “When a venue is taking 35 percent of our profit, we have to inflate our costs, which makes the customers mad, so we don’t make the money we used to make at those places, which limits the number of areas we can go to. It’s a vicious cycle.”

“We are seeing a real slow-down in growth,” Cawley told ABC News. “Some of the owners said they might hang it up. It’s too hard. ... It would be a real shame if regulation and red tape ended up stalling this revolution in American cuisine.”