I was a victim of online sextortion in high school. Here's what I want parents and kids to know

Taylor, a 25-year-old woman from Maryland, was a freshman in high school when she received a message on Facebook asking if she had ever sent a nude photo.

What followed next were thousands of messages, threats and demands for nude photos from the person on the other side of the computer, a person whose identity Taylor did not know.

Now Taylor, who asked that her last name not be used to protect her privacy, says she is sharing her story of being a victim of sextortion in hopes of educating parents and kids and helping prevent what happened to her from happening to anyone else.

Sextortion is a crime in which people adopt fake identities online, coerce victims to send nude photos of themselves and often try to get the victims to pay money in exchange for a promise not to post the photos, according to the FBI. Over the past several years, the agency has warned of a "huge increase" in the number of children and teens being the victims of sextortion crimes.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children -- which recently launched a public education campaign about child sextortion -- reports that between 2021 and 2023, it saw a 300% increase in reports concerning "online enticement," including sextortion, which happens across all social media platforms.

"My grandparents raised me and they didn't know much about internet safety," Taylor told "Good Morning America." "It was always like, 'Don’t talk to strangers,' but really for my generation, who really was a stranger to us? Because now we have this online platform where we can connect with anybody in the world."

How a yearslong sextortion scam began

Taylor was 15 years old and on her way home from dinner at a local restaurant when she said she saw a message notification on Facebook, the main social media platform she used at the time, in 2014.

She ignored the message, but after receiving a few more seemingly urgent messages from the same account, which she said had no profile picture, she responded.

"Finally I messaged them back and I was like, 'Who are you? What do you want from me,'" Taylor recalled. "And they immediately responded and said, 'Have you ever sent a nude photo?'"

Taylor told "GMA" she had recently sent a topless photo of herself to her boyfriend at the time. She said she sent the single photo to him on Snapchat, a then-newly launched social media platform where photos are deleted after they are opened.

Taylor said she asked her boyfriend if he had somehow saved or shared the photo. When he told her he had not, she replied to the stranger messaging her on Facebook.

"I messaged this profile back and said, 'Look, can I see the photo?,' Because I knew that if I if I saw the photo, I would know it's me," Taylor said. "And I just remember them replying and saying, 'That's none of your business, and now you're going to do whatever I want or I'm going to share this photo online and I'm going to send it to your friends and family and everyone's going to hate you."

After receiving that message, Taylor said she sent the three nude photos of herself that were demanded of her at the time.

What it feels like to be the victim of sextortion

For the next two years, Taylor said she felt like she lived a double life.

Outwardly, she went about her normal life of going to school and interacting with friends and family.

Inwardly, she said she was a prisoner to the demands for photos she received via Facebook messages and text messages from a person she now knows is Buster Hernandez, a California man who was sentenced in 2021 to 75 years in federal prison for the actual or attempted sextortion of at least 375 victims, according to the U.S. Attorney's Office in the Southern District of Indiana.

Taylor was Minor Victim 6 in the case against Hernandez, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney's Office confirmed to ABC News.

"He made me my very own Dropbox [file] that I had to put everything in and it was, 'This is what you are to do for me today. This is how you will pose. This is what you will wear. This is what you will use. This is how you will look," Taylor said. "And at the end of it, my face had to be in everything."

Taylor said some weeks she would hear from Hernandez once or twice, while other weeks he would text her nearly daily. While he mostly demanded photos, other times Hernandez would text just to talk and ask her how school was going, according to Taylor, who said the friendlier messages caused trauma bonding.

Until Hernandez's arrest in 2017, Taylor said she did not know anything about his identity, meaning she did not know whether the person messaging her lived down the street or across the globe, whether he was a man or woman, or whether he was a stranger or someone she knew.

"Very early on, within the first year, I came to terms with, I probably won't ever be able to get married. I probably won't ever be able to have kids. I wouldn't be able to live a normal life because it didn't matter what I had going on in my life, whatever he wanted, I had to do it," Taylor said, adding, "I just had come to terms with this was going to be the rest of my life, and I had to be OK with that."

Taylor said answering Hernandez's demands and hiding it all from her family and friends became the focus of her entire life.

"I would lay in bed and I would just be like, 'Why?' ... I didn't understand, what did I do so bad in this life or a previous life that I'm now living this?" Taylor said. "So, it was a lot of emotion, but a lot of like, power through and get it done, because this is your life now, and this is what you're doing."

How Taylor's sextortion victimization stopped

The only person Taylor said she confided in early on about the messages she was receiving online was a friend who encouraged her to tell her school resource officer.

Taylor said she went to the officer twice and both times was told to ignore the messages and that there were no resources for help.

Taylor's decision to never speak about the messages she was receiving changed her junior year, when she said Hernandez began to send increasingly threatening messages and asked her to film a sex tape with her boyfriend at the time.

After telling both her boyfriend and her grandparents about the messages she'd received for the past two years, Taylor said she stopped communicating with Hernandez, went off social media and changed her cell phone number.

Within around one week, Taylor said over dozen fake profiles using her name were created on Facebook -- with her friends, family members, teachers, school administrators and more added as friends -- and dozens of nude photos and videos were released.

"Every time he shared images, and any time he shared any of the content, I would look through it to see, 'Is there that original photo?' And there never was," Taylor said. "He never had an original photo. It was just the threat of it."

Fearing for her own safety and for her family and friends, Taylor said she called the non-emergency line of her local sheriff's department, who dispatched a deputy to her home who specializes in internet crime.

"I answered the door and this deputy is standing there in the same sheriff's department uniform that my SRO [school resource officer] wears," Taylor recalled. "And all I could think of in that moment was like, oh my God, I have been waiting two years to meet you. Like, I didn't think you existed. I was told you didn't exist."

Over the next several months, Taylor worked with the deputy as he tried to track Hernandez, who continued to intermittently create new social media profiles using Taylor's name and post more compromising photos.

Finally, in 2017, Taylor said she got a phone call from the deputy, who told her he was in California at the time.

"I remember him getting really quiet for like a minute on the other end of the phone, and I was like, 'What's going on?' And then all of a sudden he's like, 'We got your guy,'" Taylor recalled. "I remember just literally hitting my knees and sobbing because I was like, my nightmare is over. I have waited so long, and it's finally over."

By the time Hernandez was sentenced in 2021, Taylor, who was first messaged at age 15, was 22 years old.

What parents and kids should know

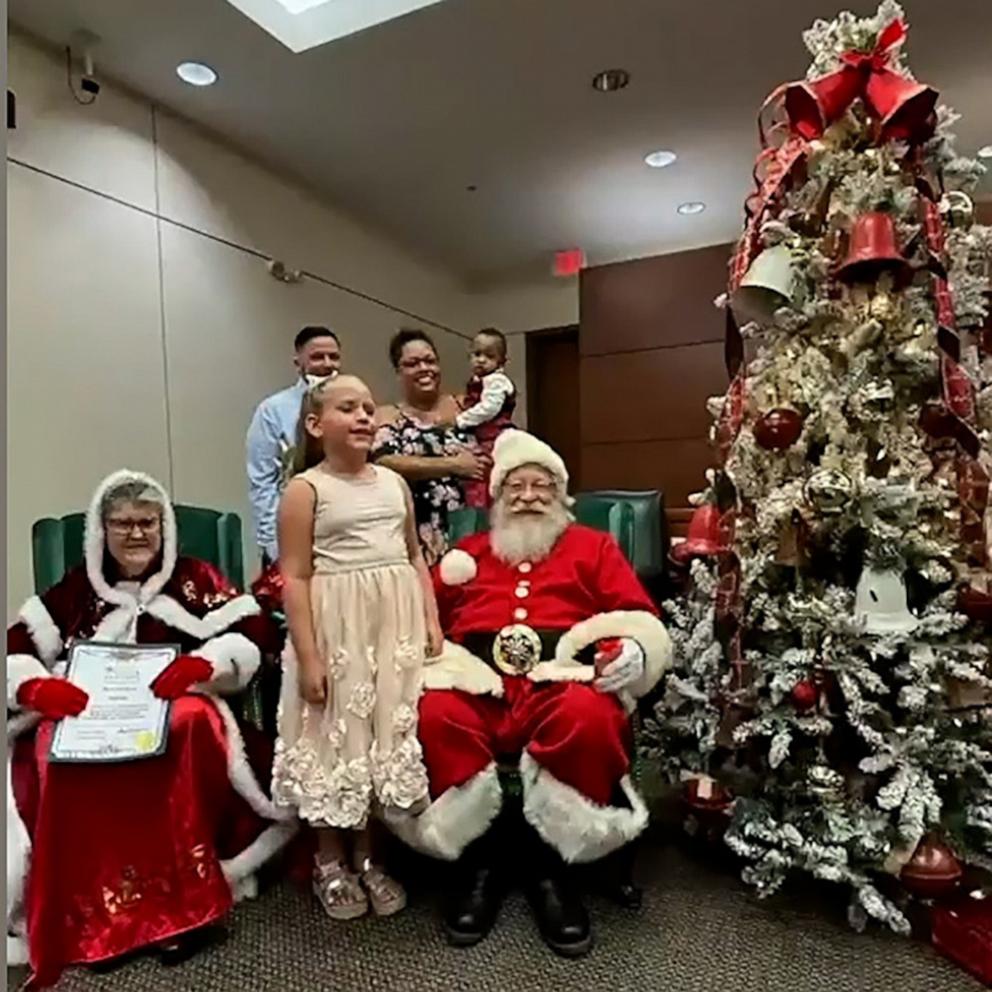

Taylor recently began to share her own story after taking time to work on her own healing and to pursue her dreams -- graduating from nursing school.

As a volunteer for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, Taylor participates in trainings for school resource officers to help them spot sextortion and support students who are victims.

In January, Taylor traveled to Washington, D.C., to speak out as chief executive officers from some of the biggest social media companies -- including Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg -- testified in a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on federal legislation to safeguard children online.

Following that hearing, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, announced it would start testing new features to help protect minors from sexual extortion and intimate image abuse. In an April 11 announcement, the company said it would begin testing a feature in Instagram DMs that "blurs images detected as containing nudity and encourages people to think twice before sending nude images."

The nudity protection feature will be turned on "by default" for teens under the age of 18, the company said.

In an emailed statement, a Meta spokesperson highlighted the platform's tools to fight sextortion, calling it a "horrific crime."

“Sextortion is a horrific crime and we’ve spent years building technology to combat it and to support law enforcement in investigating and prosecuting those behind it," the spokesperson said. "This is an ongoing fight where determined criminals evolve their tactics to try and evade our protections, which is why our expert investigators monitor new trends so we can improve our systems, and why we share signals with other tech platforms so they can take action too. We recently announced new tools to protect teens from financial sextortion, and we’re partnering with the Department of Homeland Security’s Know2Protect campaign to prevent and combat child exploitation.”

Meta has a Sextortion hub within its Safety Center resource that parents and teens can use to educate themselves on combating sextortion.

Both Facebook and Instagram are also founding members of Take It Down, a free service created by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to help people remove or stop the online sharing of intimate images taken before the age of 18.

Taylor said she encourages parents to educate themselves and their kids on online dangers like sextortion and to make sure their child has a trusted adult to confide in, whether it's them or someone else.

Taylor also said parents should talk to their kids about what healthy boundaries look like in friendships, both online and in-person.

"Telling your kids not to talk to strangers online ... that doesn't work anymore," Taylor said. "Identifying those healthy relationships and unhealthy relationships when it comes to not just intimate relationships, but friendships online, or friendships in general, I think that's probably the biggest advice that I could give."

For kids, Taylor said her advice is to be "vigilant" about what they share online and who they talk to, and to know that they can speak up and ask for help.

"Know that you're not alone," she said. "If you went through this, or are going through this, there's help out there. There's hope out there. There are people that will believe you and will want to help you and who you can trust."