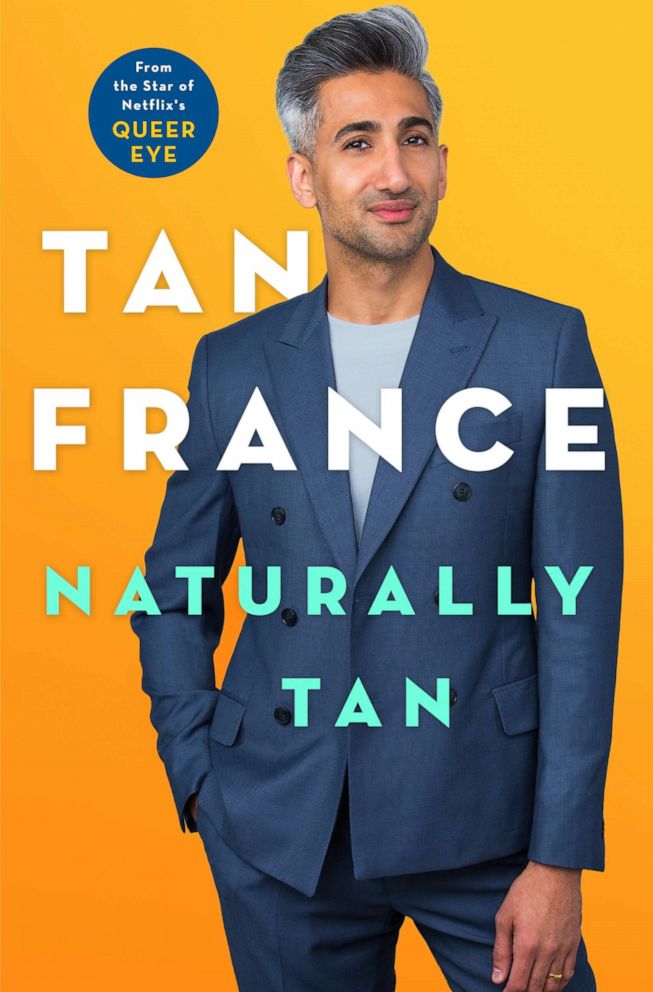

'Queer Eye' fashion expert Tan France on how he learned to embrace being 'different'

Tan France, the fashion expert on "Queer Eye," released his book, "Naturally Tan: A Memoir." Here, France details his experience growing up gay, Muslim and South Asian in the predominantly white South Yorkshire, England. He also shares how feeling "different" shaped his world view and developed his passion for style. You can read the full excerpt below.

Straight people love to ask, "When did you know you were gay?" Maybe some people do have an epiphany. I am not that person. For me, when somebody asks me this question, it's the same as someone asking, "When did you know you were a boy?" or "When did you realize you were a human?"

Because I breathe.

I've always known.

"It's a quality I like about myself and don't plan to change anytime soon."

It sounds cliché, but I never had that Oprah aha moment. I always knew that women weren't for me. Don't get me wrong—I've always loved women, in that I wanted to surround myself with females, and they are the people who have molded who I've become, but there was never a time when I thought a woman was a viable option for my romantic future. I also never thought that a man was not an option. Even when I was very young, I assumed I would get married one day and it would be to a man. Why wouldn't it be so? It was men I was attracted to and loved, so it stood to reason that I would eventually marry one. I never thought that might not be legally possible, nor did I think it was problematic. I was very matter-of-fact about it, as I was with most things in my life, and still am. Throughout this book, you'll realize that maybe I'm not the "zero f---s given" kinda guy, but I'm definitely the "very few f---s given" guy. It's a quality I like about myself and don't plan to change anytime soon.

I grew up in a small English county called South Yorkshire, which is in the north of the country. It was mostly white; there were maybe ten other South Asians in my school and one black student. My parents were both born and raised in Pakistan until they moved to the UK with their respective families in their teens. My dad's family moved to the north of England in the 1950s with very little money. Eventually, he saved enough money to buy a home and start a business, and he became relatively successful. My mum's family was already in a nearby town, and my parents met and—this is very bold of them—had what is a called a "love marriage." In a culture that favours arranged marriages, sometimes even among cousins—(Calm the frack down. I know, I know, that sounds crazy, but I can't get into that right now. More on this later.)—this was an entirely unconventional way to start their life together. We lived in a home adjoining my father's brothers, so I was raised alongside female cousins that I one day might be called upon to marry.

Our home wasn't super religious, but we had a profound cultural connection to our Muslim heritage. Every day, I would get out of school by 3:30, get home at 4:00, and then go to mosque, where I would stay until 7:00. It was like that every day, Monday through Friday, and weekends, too. Even when white school was on vacation, it didn't matter. Brown school doesn't take any time off.

At the age of six or seven, we started to wear modest clothes called shalwar kameez. The pants have an elasticated waistband. If you open them up, they're massive, one size fits all, and they are really bunchy and baggy, tapering toward the bottom with a cuff like a harem pant. Over them, you wear a tunic—for men, plain and over the knees or longer, and for women, looser still. As an added layer of modesty out of the house, women also wear a jilbab—essentially, a large sack. There could be a gust of wind and still you will not see what you should not be seeing.

The only time I was permitted to wear anything other than shalwar kameez was at school, where I wore a uniform, or when we broke out the "fancy Western clothes" permitted for events like weddings or birthday parties.

Beyond this, we were supposed to conduct ourselves with modesty in all aspects of our lives. We weren't allowed to have sleepovers or hang out with our friends outside of school—and we weren't allowed to date. Of course, this was no problem for much of my adolescence, because I didn't like girls. Actually, not being able to date was a blessing at the time, as it made it so easy to cover up the fact that I wasn't into girls. I just couldn't date. I'm single because I'm not allowed to date and not because I don't fancy girls. So that's that. Nothing to see here, folks.

There were five of us—I have two sisters and two brothers—and I was the baby. Out of all my siblings, I was always the surest of myself. My parents worked a lot, and so when they weren't around, I watched a lot of TV that was not permitted, like Melrose Place, Beverly Hills 90210, and ER, all of which had much more mature subject matter than a child should be watching. They dealt with subjects like sex and drug use, which my parents would have been completely shocked to discover I understood, never mind that I was learning about these things from TV. These topics were never discussed in our culture. Because I watched so many shows, I became weirdly worldly wise. My vocabulary was different; I knew things even my oldest siblings didn't know. I was definitely the cockiest one of the family. I would correct other people's spelling and grammar and the way they'd speak. I was the obnoxious sibling. I was a nightmare.

It was clear from an early age that I was "different" and that I had a particular affinity for personal style. Growing up, my favourite movie was Dirty Dancing, which no other eight-year-old boy was obsessed with. (Their loss. That movie is still incredible and holds up like no other.) I also had lots of Barbie dolls, but no one outside the house knew about that, which is probably a good thing, as my school was definitely not ready for that in 1990. Weirdly, my dad got them for me. (I know that sounds insane, but here goes.)

Text credits © 2019 by Tan France and reprinted by permission of St. Martin's Press.

Editor's note: This was originally published on June. 3, 2019.