This woman was the first wheelchair rider to become a teacher in New York City

A captioned version of this video will be available next week.

Herstory Lessons pays tribute to women whose accomplishments are hidden from history, but who have made an impact on the world. In celebration of Women's History Month, "GMA" is highlighting these hidden female figures who have made a critical contribution to our culture.

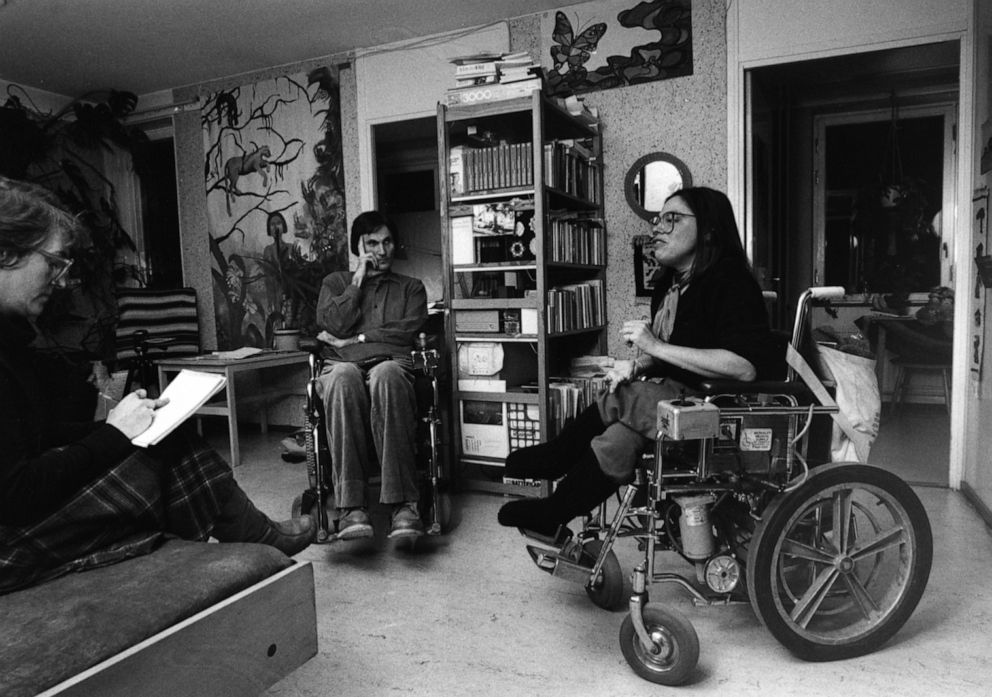

Judith Heumann was the first person in a wheelchair to be hired as a teacher in the New York City school system.

She eventually became one of the highest-ranking people with a disability in the U.S. federal government, working for both Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

Heumann joined other activists with disabilities on the frontlines, demanding inclusion and accessibility.

"Regardless of the type of disability we had, and regardless of the type of discrimination that we were experiencing, we need to fight for equality and justice together," Heumann told "GMA."

She is best known for organizing the longest federal building sit-in in American history, the 504 Sit-In of April 1977.

Her work as an unflinching activist paved the way for the landmark 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

Heumann is the daughter of German-Jewish immigrants who escaped the Holocaust, and grew up in Brooklyn, New York.

At the height of the polio epidemic of 1949, she contracted the virus at just 18 months old and was paralyzed by the disease.

"I have limited use of my hands and arms, and I don't walk. To this day, people stare frequently," Heumann said.

I have limited use of my hands and arms, and I don't walk. To this day, people stare frequently.

At the time, it was common for parents to institutionalize children with disabilities and a doctor recommended that for Heumann, but her parents refused to send their daughter away.

As Heumann got older, her mother tried getting her admitted into kindergarten, but many schools denied her, claiming she was a "fire hazard."

Instead, she received 2 1/2 hours of homeschooling a week until she was in the fourth grade.

While her neighborhood friends embraced her, one day on her way to a candy store, "This boy asked me, you know, are you sick?" Heumann said.

The incident which she details in her book, "Being Heumann," left her feeling like "a butterfly becoming a caterpillar."

"It made me realize that some people looked at me really differently," Heumann said. "I started seeing myself in some way as not being the same."

Eventually, Heumann was accepted into a New York City public school program for students with disabilities. But her experience was far from normal. She said her classes were hidden away in the basement and she felt disconnected from the rest of the school.

But Heumann persisted, becoming the first student from her grade school program to go to high school -- and eventually college.

When she got to her dorm room at Long Island University, she said she had to ask for help every single time she entered the bathroom or exited the building.

Yet, Heumann’s dreams never dwindled: she wanted to become a teacher.

But since there had never been a teacher hired in the New York City school system who used a wheelchair, she knew there would be more barriers to overcome.

During a physical assessment for her teaching license, she was asked to walk in front of doctors and said she was asked questions such as "How do you use the bathroom?"

She was later denied her license by the New York City Board of Education.

That’s when Heumann reached out to the American Civil Liberties Union to file a discrimination case. But the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not protect disabilities, so it told her it was unable to take up her cause.

She told her story to a friend who was a stringer for The New York Times. A day later, a reporter reached out and soon, two articles were published chronicling her experience trying to get her teacher’s license.

I was qualified to teach, there was a shortage of teachers and the Board of Ed should hire me. And that I felt was really a phenomenal opportunity.

"The editorial basically said I was qualified to teach, there was a shortage of teachers and the Board of Ed should hire me. And that I felt was really a phenomenal opportunity," Heumann said.

More newspapers published articles on Heumman’s plight, one powerful headline reading, "You can be President, not Teacher, with Polio."

Then at age 22, Heumann took her case to federal court in 1970.

"Constance Baker Motley ... was the first African-American woman to serve on the federal bench. And she was the judge that we got. And she really, you know, made the difference because she directed, she encouraged the Board of Education to reexamine their decision," Heumann said.

After the Board of Education settled with her out of court, Heumann got her license to teach.

That’s when Judy Heumann became the first teacher using a wheelchair to be hired in New York City.

After three years of teaching, Heumann began working for the Center of Independent Living in Berkeley, California, and was later offered a position to work for U.S. Sen. Harrison Williams in New Jersey.

But in 1975, she endured a stunning indignity on a flight to Washington, D.C., being forcibly taken off a plane and arrested for flying without a companion.

There were proposed airline regulations aiming to restrict people with certain disabilities from flying independently. However, those restrictions had not been enacted. Still, Heumann was arrested and told her actions were illegal.

"Rosa Parks gets arrested for not being willing to move to the back of the bus. And I wasn't about to acquiesce to what I consider to be really inappropriate violation of my rights," Heumann said.

The police who arrested her asked for her ID. She obliged and showed them her U.S. Senate badge, and Heumann said their tone immediately shifted. She was released but missed her flight.

There was finally a spark of hope after the decades of discrimination with the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act read, “No otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States, as defined in section 706(8) of this title, shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance…”

It was the first time the government acknowledged Americans with disabilities were being discriminated against at an alarming rate -- and had been for years.

But Heumann teamed up with other activists with disabilities to draw attention to the legislation.

Together, they organized the longest federal sit-in in U.S. history in April 1977 to demand the act be signed into law after being delayed for four years.

"It brought deaf people and blind people and physically disabled people, people with all kinds of disabilities, together," Heumann said.

Shortly afterward, the legislation was finally signed into action.

Years later, in 1990, activists took to the United States Capitol building urging Congress to pass the momentous and sweeping Americans with Disabilities Act. A precedent had been set with the 504 Sit-In, and people with disabilities were continuing to rally together to fight for their rights.

The ADA would protect the rights of people with disabilities and require adaptations made across the country to include them in public life, from jobs to schools to public transportation.

In the powerful demonstration, people left their wheelchairs and crutches behind to climb up the Capitol steps.

On July 26th 1990, the ADA passed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.

"The Americans with Disabilities Act let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down. We're talking about a change in the physical environment ... accessible buses, accessible train ramps, movie theaters ... wheelchair technology for people who are deaf or blind," Heumann said.

In 1992, the Clinton administration offered Judy Heumann a job at the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services. She became the highest-ranking disabled person at the time in the U.S. government.

In 2010, the Obama administration appointed her special advisor to Disability Rights International's efforts.

Huemann used her position in life to elevate others with disabilities, advocate for fair treatment and propel the idea of an accessible world for all to a global audience.

"I believe what I've meant for others is an example of how people can live their lives being open and honest and fighting for justice ... and we need to never give up on that," she said.