Herstory Lessons: Female pilot was prepared to give her life to stop the 9/11 attacks

Herstory Lessons pays tribute to women whose accomplishments are hidden from history, but who have made an impact on the world. In celebration of Women's History Month, "GMA" is highlighting these hidden female figures who have made a critical contribution to our culture.

On September 11, 2001, Heather "Lucky" Penney was chosen for a high-stakes mission that could have changed the course of American history.

Her goal was to intercept United Airlines Flight 93, the flight then-believed to be heading to another target such as the U.S. Capitol, but now known as the hijacked plane that crashed in Pennsylvania.

What she didn’t know at the time was that her father, a United Airlines pilot, could’ve been flying that very plane.

When asked if she’d do it all over again, Penney told "GMA," "Absolutely. Even with daughters, even with my life now."

Penney was born at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona in 1974.

"Aviation has always been in my blood. As a matter of fact, I'm a third-generation pilot," Penney said.

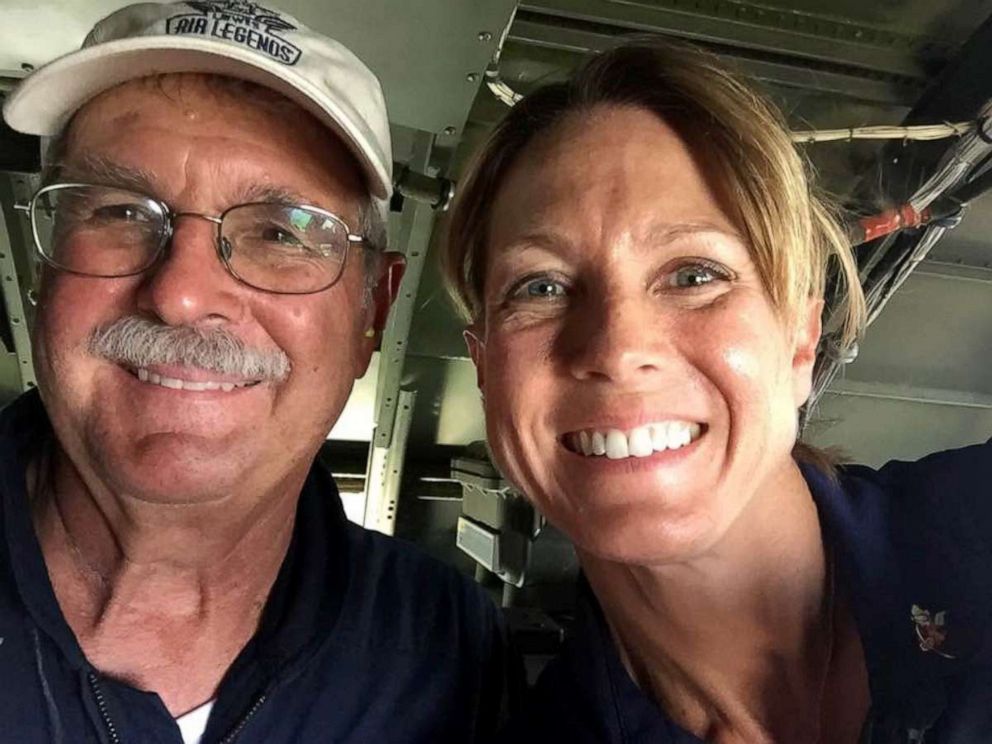

Her father, John Penney, was a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who had flown during the Vietnam War before he later became a commercial pilot for United Airlines.

"I learned early on that as long as I stayed quiet and didn't touch anything that my dad would let me tag along," Penney said.

Penney got her pilot’s license at 18. But it wasn’t until she went to college in 1992 that she learned women weren’t allowed to be fighter pilots. Realizing she couldn’t pursue her dream, she turned to liberal arts, majoring in English. Then, in 1993, Congress opened combat aviation to women.

"I didn't learn about this change in the law that allowed me to enter the cockpit until I was in graduate school," Penney said.

In 1996, Penney began following in her father’s footsteps. She applied to and was hired at the District of Columbia Air National Guard.

Two years later, Penney began her career when she was commissioned as an Air Force officer. She started undergraduate pilot training in Texas, and earned her aviation nickname.

"Lucky is my call sign. Realistically, it's a play off of my last name, 'Lucky' Penney ... It's given to you by your fighter squadron after you become combat mission ready," Penney said.

Three years after Penney stepped into the cockpit -- and being among the first wave of America's female fighter pilots -- 9/11 happened.

At the time, Penney was a rookie pilot in the 121st Fighter Squadron of the D.C. Air National Guard, which hadn't yet had a female F-16 fighter pilot before.

"It's incredibly physically demanding and very intellectual," Penney said of flying an F-16.

Penney described the morning of 9/11 as crisp and clear, with blue skies. She was in a meeting when someone said an aircraft flew into the World Trade Center. At first, like much of the world, they thought it was a tragic accident.

"It wasn't until he came back the second time and said, 'A second aircraft flew into the second World Trade Center. It was on purpose,'" Penney said.

Penney said at that time in Washington, D.C., there were no missiles in place to defend the Capitol, there were no armed aircraft standing by and that there was no system for something like this.

"So the Secret Service calls us and gives us that authorization to launch -- our director of operations at the time, he was a major, Marc Sasseville, [he] looked at me and said, 'Lucky, you're with me,'" Penney said. "And he told Dan Caine and Brandon Rasmussen, who took off after us, he told them to wait until they had missiles."

In the meantime, someone needed to get airborne to stop the hijacked plane. Penney and Sasseville would fly together but in separate planes. It was not just a pact. It was a potentially fatal mission.

"We all knew that this was a one-way mission ... if we were successful, we wouldn't be coming back," Penney said. "[We] were prepared to sacrifice our lives to protect our nation. We had no missiles, no armament onboard. And so we knew that if we were able to find this airliner that we would have to crash our jets into [it] to prevent it from getting to the United States Capitol," Penney said.

In the tense and confusing moments after the New York and Pentagon attacks, their mission was to stop Flight 93 from hitting another location and to take it down, along with everyone on board.

It never occurred to me that my dad, who was a pilot for United at the time, could have been airborne on that day.

"It never occurred to me that my dad, who was a pilot for United at the time, could have been airborne on that day. He had been flying routes up and down on East Coast," Penney said. "My mother figured it out weeks afterwards that that actually could have been him in the cockpit. As for me, that thought never crossed my mind. And if it had, it wouldn't have changed it."

Penney accepted her fate and the fate of those on board. All of their lives would have to be sacrificed for the possibility of saving others.

As luck would have it, she would not have to carry out that mission. The heroic passengers and crew of United Airlines Flight 93 fought the terrorists to regain control and crashed the plane into a field in Pennsylvania.

"The true heroes, if you think about it, are the passengers on Flight 93. And the first responders who rushed into the buildings, not just stood outside. Or the people who are in the buildings who helped each other, or even the workers who cleaned up Ground Zero, knowing that that work would eventually kill them. But doing it anyways because our nation needed the healing," Penney said.

"In the weeks and the months that followed, I did what everyone else in my squadron did, which was fly, combat air patrols ... I didn't really feel like I needed to process anything because I didn't feel like what I did was special or unique," Penney said.

I didn't really feel like I needed to process anything because I didn't feel like what I did was special or unique.

She went on to fly two combat tours in Iraq and eventually took a job at Lockheed Martin, where she worked to communicate between engineers, programs and Air Force customers.

Today, she’s a senior fellow at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, and works on defense policy, research and analysis.

She’s also a mom to two girls. And she still flies.

"We all have that capacity but we don't have to wait for history, that we can all do something that changes somebody else's life today," Penney said. "And it might be a minor kindness. It might be just having a little bit extra courage to do the right thing. Or overcoming our own fears again to do that thing that needs to be done."