If you’ve finished our “GMA” Book Club pick this month and are craving something else to read, look no further than our new digital series, “GMA” Buzz Picks. Each week, we’ll feature a new book that we’re also reading this month to give our audience even more literary adventures. Get started with our latest pick below.

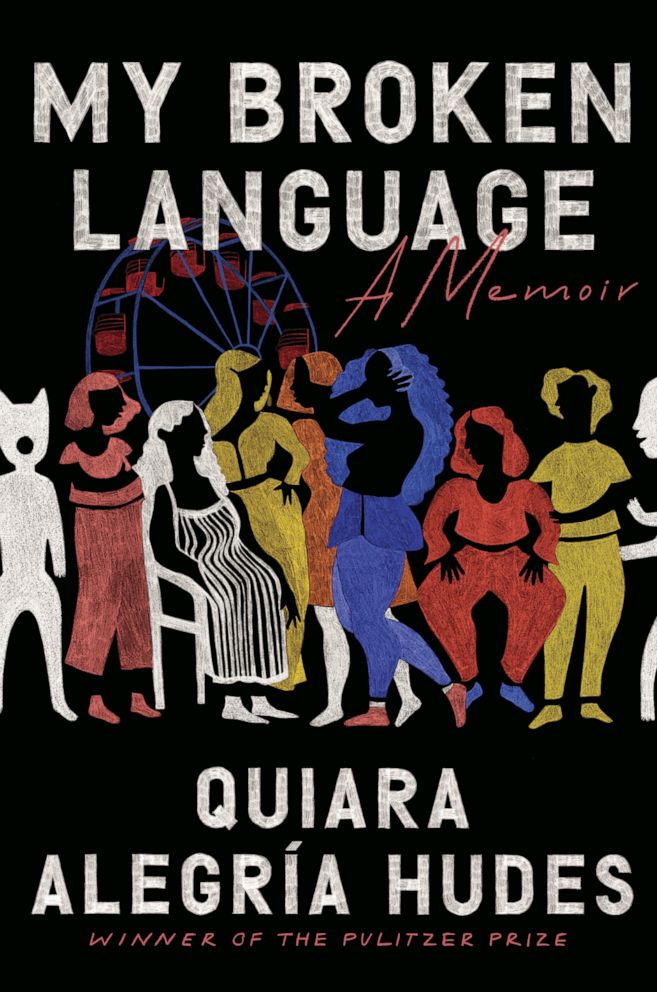

This week’s “GMA” Buzz Pick is “My Broken Language: A Memoir” by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Quiara Alegría Hudes.

Hudes’ coming-of-age novel explores how she found her voice while growing up in a Puerto Rican household amid the backdrop of an ailing North Philadelphia barrio.

Through her experiences from childhood, Hudes puts a spotlight on the relationships she had with the women in her big Puerto Rican family, the feelings she had about being bilingual and mixed race and societal issues she and her family faced.

“In this book, I take every language from my life, even the language of the spirits, to describe surviving childhood loss in Philly and becoming an artist,” Hudes told “Good Morning America.” “It’s a memoir of growing up in Philly in the '80s and '90s, when AIDS and addiction touched my family, and yet how our dance parties, prayers and loud music filled me with resilience and joy.”

Get started with an excerpt below.

Read along with us and join the conversation all month long on our Instagram account -- GMA Book Club and #GMABookClub

*****

A Multilingual Block in West Philly

Dad was hurrying mom in English. “Let’s go, Virginia,” as he leaned against the tailgate sucking an unfiltered so hard I heard it crackle all the way on the stoop. Mom propped the screen door with her foot, ordering me to carry out boxes in snaps, gestures, and screams. And Titi Ginny was telling mom to pay dad no mind in Spanish. “Siempre tiene prisa,” she whispered with a tilted smile, turning dad’s impatience into a sweet little nothing.

My brat pack came to wave me off and started in on the obscene gestures whenever mom turned her back. Chien was first- generation Vietnamese. Ben and Elizabeth, first-gen Cambodian. Rowetha lost her Amharic after leaving Ethiopia. We all spoke English, unlike our parents, who all spoke different languages from one another. This was my West Philly crew, my pampers– to–pre-K alphabet soup. I assumed all blocks everywhere were like it—as many languages as sidewalk cracks, one boarded-up home for every lived-in, more gum wads than dandelions. But mom told me no, nature would reign at our new rental house on a horse farm.

Titi Ginny unlatched the screen so it slammed, and handed me a pastelillo grease-wrapped in paper towel. A snack for the drive. I wanted her to re-create our current layout in the new spot, to move next door so I could sneak across the alley and watch cartoons in her lazy boy. There was a spot between two pleather cracks, duct-tape repaired, where my butt fit perfectly. My Sunday morning throne. But mom said there were no alleys where we were moving, and no such thing as next door either. That gave me something to think about.

Anyway, Titi Ginny’s softball team was waiting in Fairmount Park and she had to be on second base in an hour. So she rolled down her driver’s side and promised to visit the farm, my big cousins in tow. Mary Lou, Cuca, Flor, Big Vic, Vivi, and Nuchi. She’d cram all their stinky teen butts in her backseat, and they’d see the country for the first time. “Bring Abuela and Tía Toña, oh, and Tía Moncha, too,” I said, marveling at the prospect of hanging with my fam outside of Philly. Titi Ginny turned the key and every version of dios-te-bendiga rolled off her tongue. There were a million ways to say god-bless in Spanish. Dios te cuide, dios te favoresca, dios te this and te that. There was only one way to say it in English, and you only said it after a sneeze. Then off she went before off we went.

Dad slammed the tailgate and mom teared up in the pleather passenger side. “Extrañaré a mi hermana.” Dad stayed quiet, probably didn’t understand. But I knew the Spanish word for missing someone sounded like the English word for strange. Sandwiched between them, I sensed mom’s worried profile. She had talked the move up for months, but saying goodbye to a sister was a whole ’nother thing.

“Then why do we have to move today? Can’t we finish out summer on the block?”

“Because, Quiara, I been stuck a city girl since I was eleven. But before that, before I came to Philly, I had a whole farm to myself. Mami gets to be with nature again, where she belongs, like in Puerto Rico.” And her tired eyes made room for a little spark. How she told it, mom had been changing scenes all her life, same as geese veeing over the art museum. There was always a next stop full of new promise. Even Abuela’s memories about PR were made of a million places—towns, cities, and barrios. Too many to keep track. This time, I got to join mom’s migration.

Pulling away from the narrow block, the rearview showed my crew double-dutching and playing shoot-out. No final waves, hollers, or stuck-out tongues. Whatever’s the best language for saying bye, I’d flubbed it cuz the city already forgot me.

The horse farm was on a twisty road flanked by woods. Perky little hills worked a number on my bladder. Despite a strong mid- day sun, the road was all green shadow thanks to trees thick and tall as god’s fingers. My old block’s trees were like zoo elephants— one or two specimens stunted by a cement habitat. But this chaos of greenery had my heart calling dibs. Monster claws made of vine and bramble reached for our truck. Far as I had known, plants began in the soil and grew to the sky. But not here, where greenery grew sideways, diagonally, and downward. “We are your new brat pack,” the woods whispered, seeming mischievous as my old crew, and also like they wouldn’t tell on you.

When I got out of the pickup, I walked to the edge of the woods and stared. “Introduce yourself. Go talk to the trees,” mom said. I ventured in, ferns feathering my shins, and didn’t stop walking till I couldn’t see the house and the house couldn’t see me. Jack-in-the-pulpits were terrariums of rainwater and drowned flies. Mushrooms shriveled and swelled. A baby toad peed a puddle in my hand. In that moist wilderness, mine and mine alone, I recited a poem aloud. An original, from memory, about the Chuck Taylors that my dreams were made of. The trees listened close, gave a standing ovation. Their mossy velvet roots invited me to sit and felt so soft I almost forgot Titi Ginny’s lazy boy.

*****

Excerpted from My Broken Language by Quiara Alegría Hudes, Copyright © 2021 by Quiara Alegría Hudes. Excerpted by permission of One World, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.