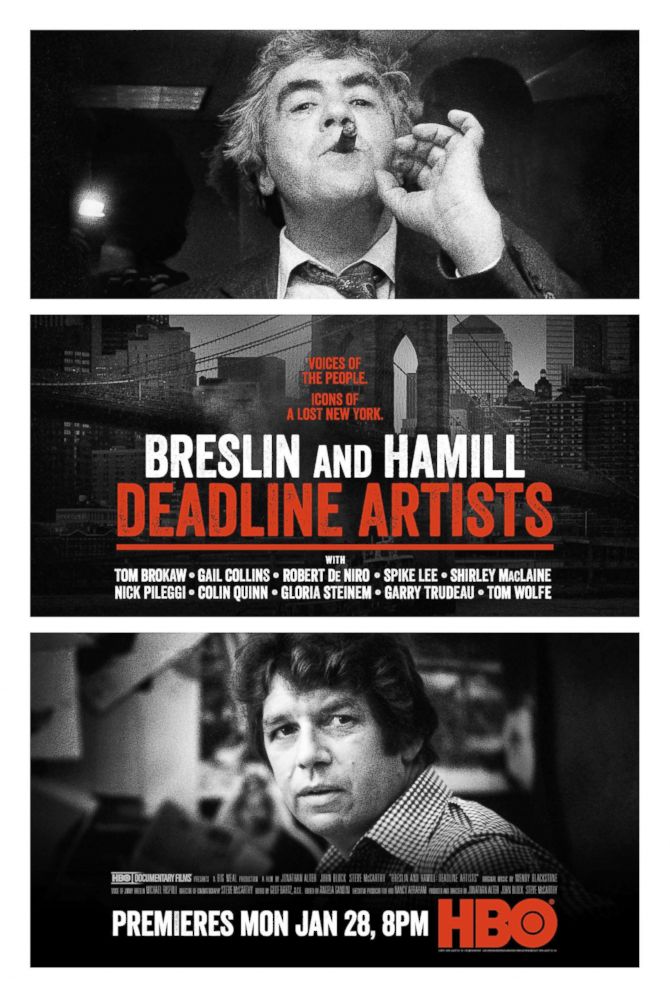

'Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists' charts the remarkable careers of two of New York City's legendary newspaper columnists

One of the most mesmerizing scenes in HBO’s new documentary, “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists,” unfolds in grainy, black-and-white footage of a 1951 baseball game between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers. New York newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin, who was then a 23-year-old rookie, covered the game.

The camera cuts suddenly to the sky as a throng of carrier pigeons burst forth from the stadium and take flight, each bearing a tiny tube strapped to its back filled with photo negatives of the game and racing furiously toward a newspaper clerk waiting near an open window at one of the city’s bounty of newspaper offices.

Long before mass media, or even national news for the most part, a city’s newspapers were its chief sources of information: its champions, entertainers and story-tellers -- exposing corruption and abuse and peddling eye-popping gossip, sports scores and sensational crime.

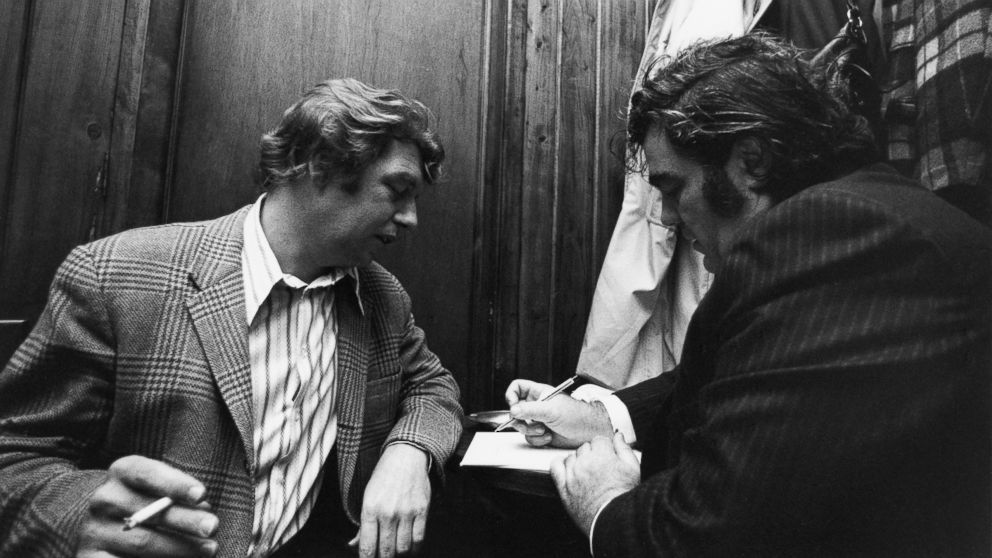

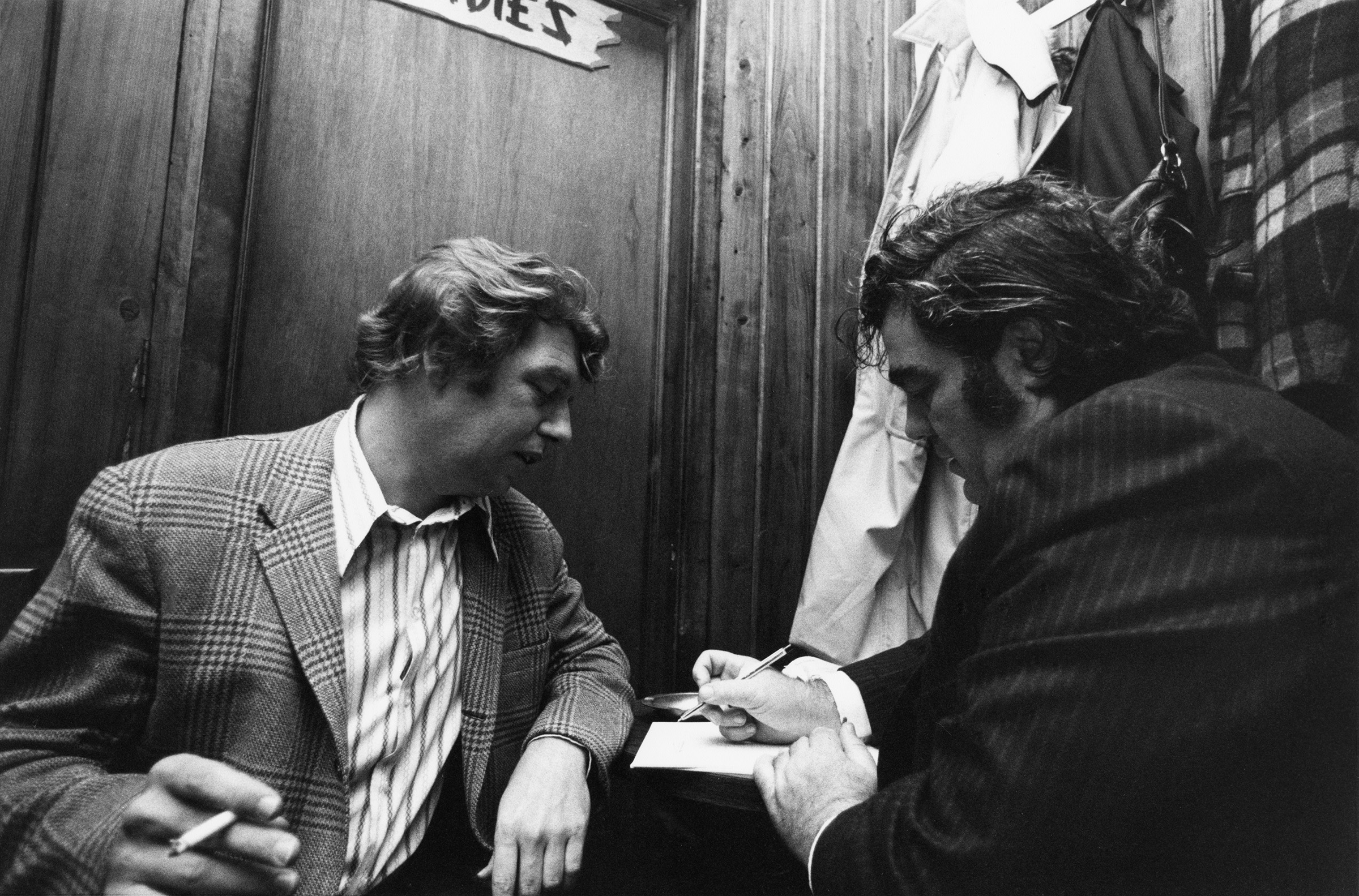

The careers of Breslin and Pete Hamill -- two of the most colorful, talented newspaper columnists of the late 20th century, who wrote about the poor and the powerful -– are the subject of a new documentary by directors Jonathan Alter, Steven McCarthy and John Block, premiering Monday.

The film is a romantic, unsentimental elegy to the last generation in American print journalism when newspapers really, truly mattered -- an era when big city columnists, the best of them at least, were more powerful than any term-limited politician, angry police chief or vindictive mobster with a standing bounty on his head.

In their own distinctive voices, Breslin and Hamill chronicled the nation’s most storied metropolis for decades with tales that illuminated the heart and the hardships of ordinary working people.

“Jimmy really admired people whose favorite four-letter word was work,“ Hamill explained to The Associated Press when Breslin died in 2017.

From the early 1960s through 9/11 and beyond, both men channeled the techniques of novel writing to elevate and reshape traditional newspaper writing. Their fable-like narratives framed big city problems in the simple stories of ordinary New Yorkers’ lives. Their columns told readers the way things really were.

Jimmy really admired people whose favorite four-letter word was work.

Between them Breslin and Hamill wrote for a variety of newspapers and magazines. But during their heyday Hamill had a column in the New York Post and Breslin had one in the New York Daily News. Both men later wrote for Newsday, and Hamill at different points in his career managed both the Post and the Daily News. For a time, the two men even had dueling columns in the Daily News.

The nimbly-paced documentary is driven by the voices of Breslin and Hamill’s industry descendants, the best and brightest of the 1990s and early 2000s newspaper voices: Michael Daly, Les Payne, Gail Collins, Earl Caldwell, Jim Dwyer, Richard Esposito, Dan Barry, Mike Barnicle and many more -- who honed their own distinctive voices in the shadows of giants.

Regrettably absent from the all-star squad of commentators are deceased New York investigate reporters Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett.

‘The Present Tense’

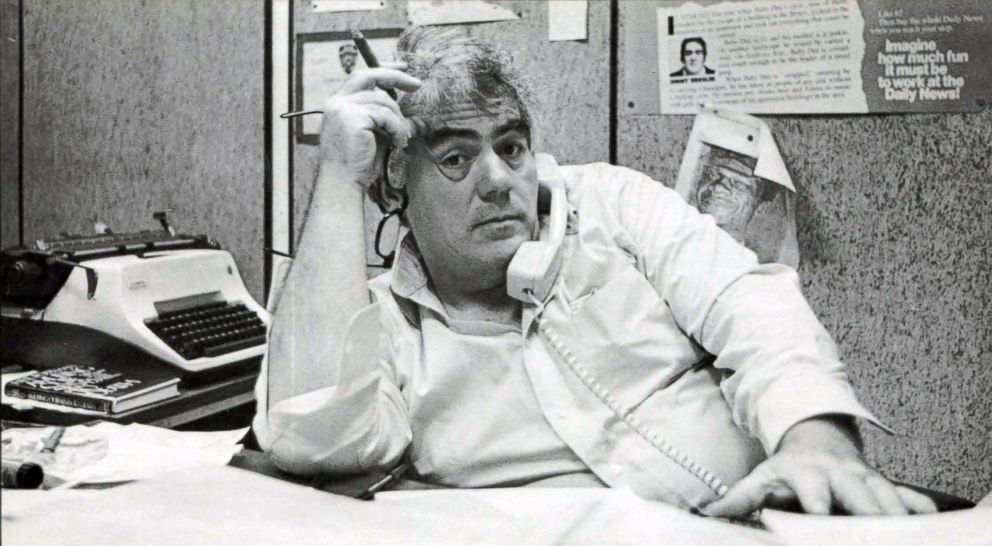

By all accounts -- none richer than his own -- Breslin was born with ink pulsing through his veins. Over time, he learned to master the art of unsentimental irony and taught himself to channel it on deadline.

When he was 8, Breslin was publishing his own, hand-drawn newspaper called The Flash. Two years had passed since his alcoholic father went out to buy rolls one day and never came home.

Then Breslin witnessed his mother’s suicide attempt.

So he wrote about it.

"When I finished The Flash I took it around to [a local] candy store and I asked them to put it in the newsstand,” Breslin recalled in his cartoonish Queens accent.

“My headline said, 'Mother Tried Suicide,'” he intones in the film. “Later I learned that the headline should have been in the present tense: 'Mother Tries Suicide.'”

Years later, when he was the most famous newspaper voice in the nation, his destitute father reappeared in his life to reach out for help.

Breslin would write that the old man blew back into his life “like heavy snow through a broken window.”

“I realized early that bad news was great, even if it involved me,” he says in the film. “I protected myself by writing about it.’”

Breslin could bend irony to his will and he summoned it for a column about the funeral for Andrew Goodman -- one of a trio of civil rights activists who were hunted down and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan during the muggy Mississippi summer of 1964.

"The first funeral for Andrew Goodman was at night and it was a lot of work,” Breslin wrote. “To begin with they had to kill him."

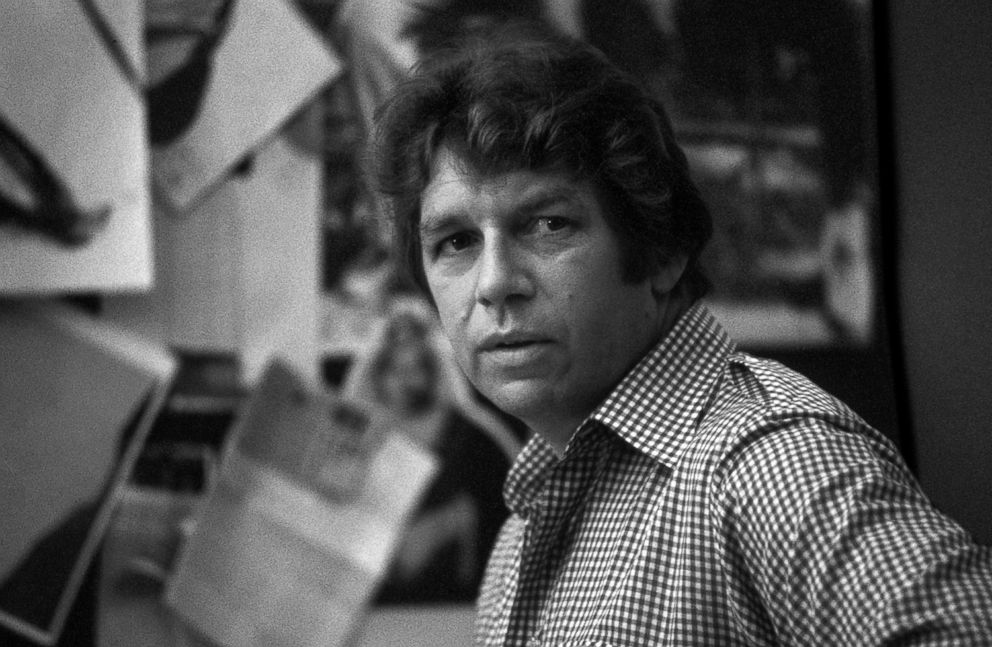

Hamill, who at 83 is now mostly home bound but still writing, is a self-educated aesthete whose literate, lyrical newspaper columns became a benchmark for a generation of writers. Hamill has long been drawn to artistry and beauty -- in art, politics, culture, literature and women. He studied Hemingway, Fitzgerald and the Lost Generation and reveres the work of Mexican Muralist painter Diego Rivera.

Bob Dylan called on Hamill to write the liner notes for Dylan's epic 1975 album, 'Blood on the Tracks,' and the Post columnist was in a New York recording studio with Dylan one day when Mick Jagger dropped by to listen in and offer some reportedly unsolicited advice to Dylan. The liner notes earned Hamill a Grammy.

By the late 1970s, the columnist's lifestyle was the envy of peers.

Among others, Hamill dated Linda Ronstadt, actress Shirley MacLaine and former first lady Jackie Kennedy Onassis – the latter two, for a time, simultaneously.

“Can you imagine a print journalist dating the most famous women in the world and a top Hollywood star -- at the same time?” director Jon Alter marveled in a recent interview with the New York Post.

In a surprise attack that still seems shocking today, Breslin broke the story exposing Hamill’s two-timing in the newspaper, stunning the city and infuriating MacLaine, who vividly recounts the incident in the documentary.

Roundly slammed for such an indelicate measure, Breslin bit back.

“I needed a column!” he barks in protest in the documentary.

Breslin and Hamill -- along with Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Jack Newfield, Gay Talese, Hunter Thompson and others -- were in the vanguard of the late 1960s New Journalism revolution.

I realized early that bad news was great, even if it involved me. I protected myself by writing about it.

Wolfe and Breslin were early recruits to write for Clay Felker's legendary New York Magazine, which -- along with Rolling Stone magazine -- was then one of the nation’s most potent hothouses for groundbreaking New Journalism.

‘Snarling and heartless’

If Breslin was the city’s reigning heavyweight pugilist, Hamill was its hometown poet laureate, infusing a distinctly lyrical rhythm into the craft of daily journalism.

“I want to see whether when I’m reading, my foot starts to keep time to the rhythm of the sentences,” Hamill says in the documentary.

Like Breslin, Hamill fell in love with newspapers as soon as he could read.

In his memoir, 'A Drinking Life,' Hamill recalls his first stint on the overnight shift at the New York Post, where when dawn came Hamill would join a group of seasoned editors at a nearby bar called Page One.

"When the papers landed on the bar, the seminar would begin. This was an often brutal analysis of stories, headlines and writing styles." Hamill loved those editors. "They were funny and merciless. About my stories. About others, their work, themselves, and most of the human race."

But he could be as exquisitely vicious as Breslin if the situation called for it.

In 1989, real estate developer Donald Trump took out an enraged, full page ad in three newspapers demanding the death penalty for five young African-American and Hispanic men whom -- it emerged years later -- had been wrongly accused, convicted and sentenced for the barbaric rape of a Central Park jogger.

Hamill read the ads, which surfaced just two weeks after the attack. He surely watched televised press conferences on TV in which Trump doubled down on his outrage. Then he weighed in.

"Snarling and heartless and fraudulently tough, insisting on the virtue of stupidity, it was the epitome of blind negation,” Hamill wrote of the ad.

“Hate was just another luxury. And Donald Trump stood naked revealed as the spokesman for that tiny minority of Americans who live well-defended lives. Forget poverty and its causes. Forget the degradation of millions. Fry them into passivity."

The two columnists -- rivals, then colleagues and ultimately dear friends before pneumonia felled Breslin in 2017 -- shared a Zelig-like ability to be right there, up close and in the arena, for some of the most pivotal moments of the late 20th century.

Forget poverty and its causes. Forget the degradation of millions. Fry them into passivity.

'A terrible discipline'

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963, Breslin was covering civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama. He flew to Dallas and worked an angle no other reporter had thought to chase.

Breslin’s "A Death in Emergency Room One" column used interviews with the surgeon and the priest who attended to John F. Kennedy in the last, desperate moments of his life to bring readers right into the emergency room that day. The column came to be seen as a landmark of New Journalism.

His haunting sketch of the scene captured the surgeon’s thoughts upon suddenly noticing that Jackie Kennedy was standing, noiseless and still, across the room.

“He noticed the tall, dark-haired girl in the plum dress that had her husband’s blood all over the front of the skirt,” Breslin wrote. “She was standing out of the way, over against the gray tile wall. Her face was tearless and it was set, and it was to stay that way because Jacqueline Kennedy, with a terrible discipline, was not going to take her eyes from her husband’s face ... She did not cry.”

Three days after the assassination, on the morning of Kennedy’s funeral, thousands in the world press were gathered in a mob outside the White House.

Breslin was elsewhere.

He tracked down and interviewed the $3.01-an-hour grave digger who dug the plot where the president’s casket would be laid. That column, too -- called 'Why, It Was An Honor' –- has become a staple of journalism school curricula.

Breslin was in the Audubon Ballroom one cold Sunday in January 1965 when Malcolm X was assassinated.

During the 1960s Hamill grew close – too close for a reporter, he later realized -- to then-New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who was agonizing over whether to run for president.

Hamill wrote the senator a brief, moving letter in January 1968, imploring him to take up the mantle of his fallen brother and seek the Democratic nomination for president.

Two days later, RFK responded to Hamill by telegram: he was ready to run.

Six months passed and Breslin and Hamill were in a Los Angeles ballroom, standing near the candidate as his press conference broke up, when Sirhan Sirhan burst from the crowd and fatally shot his mark. Breslin, Hamill and others restrained the gunman until police arrived.

“I sat on him,” Breslin recalls matter-of-factly in the documentary.

'Son of Sam'

In 1976, Breslin and the rest of the New York press were producing blanket coverage of a widening investigation into a serial killer stalking young New York City women. Initially dubbed the ".44-caliber killer," the madman was later unmasked as a pasty-faced postal worker named David Berkowitz.

But while Berkowitz was still lurking in the shadows, he began writing to Breslin at the New York Daily News – signing off with one of the most chilling pen names in city history: the “Son of Sam.”

At the urging of the NYPD, the Daily News published the letters and Breslin wrote columns about the Son of Sam, urging him to write in again in the hopes more letters would provide more clues.

When the killing continued, the columnist took to television to offer the killer an alternative to traditional criminal surrender. The Son of Sam should surrender himself directly to Breslin instead of the police.

In a sideshow that -- seen from a safe enough distance in time -- will amuse any fan of the man, Breslin went on television and comically sought to lure in his mark with false praise for the killer’s writing skills.

“I mean, he writes so well it’s a shame to waste it out there,” Breslin squawks, then briefly looks directly into the camera as if to Berkowitz himself.

“I thought Hamill wrote it to me!” Breslin insists to off-camera laughter. “It’s a well-written piece! The guy could make a living writing!”

Then, with a perfect pitch for timing, he nails a line that would become legendary.

“He probably is the first killer that I can recall who understands the use of a semicolon.”

Breslin's moving column about the 1980 murder of John Lennon tells the story of the city and its lost innocence through the eyes of the NYPD cops who first responded to the scene.

King of Queens

Nothing engaged Breslin’s energies like a fight, the bigger the better. Some of the city’s more outsized vices -- hypocrisy, cruelty, discrimination -- compelled him into combat.

He probably is the first killer that I can recall who understands the use of a semicolon.

In 1982, all three collided to create an epic tabloid showdown: The New York Police Department versus Jimmy Breslin of the New York Daily News.

That year, a 4’11 female, Hispanic cop named Cibella Bourges was fired from the NYPD after supervisors came across what was then called a men’s magazine that featured indiscreet pictures of her. Identified only as "Nina," the photos were taken before Bourges joined the force.

She was fired and then pilloried for weeks in a frenzy of lurid, tabloid headlines. It was Breslin who tracked her down and ultimately told her story.

“One day, Cibella Bourges met a photographer who gave her $150 to pose for pictures that were supposed to give men the thought of incredible pleasures,” Breslin wrote in his first shot across the bow. The photographer, Breslin wrote, later sold them “to a magazine called Beaver, which is a publication read with one hand.”

In that and subsequent columns, he blasted the NYPD so relentlessly for the way they treated Bourges, that the NYPD’s largest police union spent $16,000 on a full-page newspaper ad eviscerating the columnist as an “arrogant, amoral sop,” and slinging an absurd string of schoolyard taunts at him.

“’The Old Saloon Philosopher’ continues to attempt to malign police officers, probably because he could never pass the required intelligence and physical tests for entry into the police service,” the ad, signed by then-Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association president Phil Caruso, read.

"I offer this challenge to you Mr. Breslin,” it concluded. “Stop hiding behind your typewriter and put up or shut up once and for all."

Breslin caught the grenades and threw them all back.

“The police department should have been proud of the pictures, as they proved that at least one member of the force is in marvelous physical condition,” Breslin wrote.

In 1985, a New York state appellate division decision re-instated Bourges to the NYPD. Old footage of Bourges crisply saluting as she receives her detective’s shield is one of the most powerful moments in the film.

The police department should have been proud of the pictures, as they proved that at least one member of the force is in marvelous physical condition.

A few months before Bourges got her shield, a slender, bespectacled white man named Bernhard Goetz shot four black teens whom he said were menacing him and demanding money. Dubbed the “Subway Vigilante,” much of the city cheered Goetz, and the case sparked a national debate about race and violence. Many rushed to fund his legal defense.

Breslin saw the spectacle from a different point of view, and for some time, a very lonely one.

While Goetz was defending himself in TV interviews -- his stature and pool of support growing from one klieg-lit appearance to the next -- Breslin was out reporting and eventually he ripped the harder truth from the easier, more popular narrative.

Goetz had shot two of the young black men in the backs as they fled. That key detail changed the narrative. But it was something buried much deeper in the story of Bernie Goetz that most disturbed Breslin.

"They burned down something irreplaceable in New York this week, and there were people who looked at the ashes and termed them beautiful," Breslin wrote. "A man in the subway took out a gun and shot four people -- two of them in the back -- and then ran away. One of the two shot in the back was 19 and he will be a wheelchair for the rest of his life. And there were people who praised the gunman. As lawlessness was applauded, we in New York arrived at the sourest of all moments -- when people become what they hate."

As lawlessness was applauded, we in New York arrived at the sourest of all moments -- when people become what they hate.

'An assembly of ghosts'

For years, Breslin and Hamill wrote books, sold screenplays and honed their voices, but they always came back to newspapers. Both Breslin and Hamill were in downtown Manhattan when the planes hit the World Trade Center towers on Sept. 11, 2001. Here’s how Hamill described the scene.

“A great gray cloud billowed in slow motion, growing larger and larger like some evil genie released into the cloudless sky. Sheets of papers fluttered against the grayness like ghostly snowflakes.”

Hamill continued, “The street before us is now pale gray wilderness. There is powder white dust on gutters and sidewalks, and dust on the roofs of cars, and dust on the tombstones of St. Paul’s. Dust coats police and the civilians, white people and black, men and women. It’s like an assembly of ghosts.”

In a terrific scene captured before Breslin died, he and Hamill sit side-by-side, two lions in winter, and recall their earliest memories of learning to write from Catholic school nuns.

“Subject, verb and object -- that was the story in a whole,” Breslin says.

Hamill smiles and chimes in.

“Concrete nouns and active verbs.”

“That's what we were taught, that way,” Breslin explains. “It was pretty good teachin'!”

In the end, both men dismissed the idea that they were ever competing.

"We were doing the same thing, against the world," Breslin said.

"Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists" premieres on Jan. 28 on HBO.