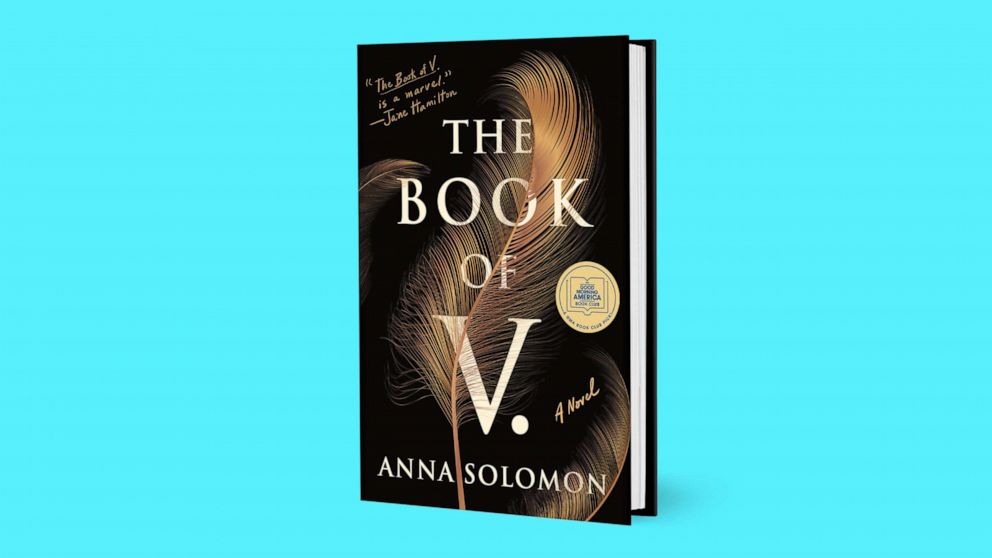

We are thrilled that "The Book of V." by Anna Solomon is the "GMA" Book Club pick for May!

"The Book of V." is told from the viewpoints of three women from different time periods and life experiences.

"This book will transport you, something we all could use these days. From a palace in ancient Persia to a wild party in 1970's Washington, D.C., to treelined Brooklyn in early 2016, you'll lose yourself in these words and get out of your head," Solomon told "GMA."

"I think a lot of readers will find some part of themselves in this book. Whether you relate most to the headstrong Esther, who does not want to become queen to Vivian Barr, a senator's wife torn between following conventions and breaking free or to Lily, a contemporary mother of two struggling to figure out what she even wants, you'll recognize and root for the characters in this book."

"The Book of V." explores desire, power, motherhood, mother-child relationships, female friendship and more.

"It's a book that can really spark conversation and maybe even debate among the women in your life," Solomon added.

Dive into the "The Book of V." right now with an excerpt.

Read along with us and join the conversation all month long on our Instagram account – GMA Book Club and #GMABookClub.

Start here with an excerpt:

BROOKLYN

Lily

The Second Wife

She hums to ward off panic, time running out to pick up one child from school while the other, smaller one throws her boots against the apartment wall. No boots! They are such nice boots, a gift from Lily’s middle brother, brand-new fuzz-lined boots in a pine-green suede. Lily would like to have such boots. She almost says this—If I had those boots I wouldn’t throw them against the wall!—but she knows it won’t help, and it’s mean, too, the kind of lording over that Lily’s grandmother did incessantly, according to Lily’s mother, Ruth, which is why, she says, Lily herself was rarely scolded as a child. Reparations, her mother jokes, though her leniency has eroded: now that Lily is grown, Ruth scolds her all the time, albeit passive-aggressively, for Lily has not become the type of woman she was supposed to come.

"I hope it fulfills you, taking care of the children all the time."

"What a variety of sponges you have!"

"You were so driven when you were younger. But maybe you’re happier now. Are you happier now?"

Lily hums to ward off her mother's voice, though it's Ruth’s favorite lullaby she’s humming, Oh the fox went out on a chilly night . . . She squats behind her daughter, pins her under the arms, and attempts to work the boots back onto her feet, thinking of Rosie being herded into the cafeteria with the snotty, sorrowful clump of abandoned first-graders.

This child, June, kicks and kicks. June, that warm and pliant month! Lily begins to sweat. Her coat is already on, her hat, her scarf. Oh the fox . . . June’s boot flies off again and Lily makes the mistake of going for it, which gives her daughter the chance to squirm away and run down the hallway toward the bathroom, where she will, in her newest favorite rite, rip off her shirt and throw it in the toilet. And he prayed to the moon . . . Lily sheds her coat and runs after her, telling herself to take a breath, get a little perspective, no one will die here—at least not today. This isn’t war, or revolution. Right? If Ro sits in the sorrowful circle, so what? She’ll look at Lily with that look, the one that seems to see into her. But so what? So she waits a few minutes, so the world is not going to end, so lots of kids have it far worse, so she’ll learn resilience, and resilience is the latest . . . and the moon . . . As she rounds the corner into the bathroom, Lily reminds herself to smile. She doesn’t want to scare June. If she scares her, they will never make it out. Lily hangs her face in a grin. But June isn’t looking at her, she is deep inside her shirt, wrestling to get it off, and Lily makes the mistake of glancing in the mirror, where she sees that her grin is terrifying. She drops it and stares at what she understands to be her face but which appears, under the fluorescence of their rental apartment’s bathroom light, to be that of an old, gray witch. Because, because, because, because, because! Because of the wonderful things . . . The tune changes as Lily enters a kind of derailment in which time goes one way and she goes another, into her small makeup box—small so as to deemphasize its importance to the girls, though there is more makeup, much more, hidden in Lily’s underwear drawer. She begins to dab and swipe at herself, thinking of the other mothers, the women who will be at the party this afternoon, a party for Lily, to teach her to sew. Lily doesn’t know any of the women well. She didn’t intend for them to throw a sewing party in her honor. But the hostess, a woman named Kyla, overheard Lily talking to another mother at preschool pickup about how she wished she could make Esther costumes for Rosie and June for Purim this year, if only she knew how to sew. This was true, in a sense. Lily did wish that she could sew. But she wished it as she wished for sleek hair or a triplex apartment: certain it would never happen and not really caring. Sure, she had a vision of herself, by herself, at a table in front of an open window, sewing. But didn’t every woman? It was a fantasy she might once have tried to parse, in a paper, theorizing about its origins in popular and literary culture and arriving at an idea that was semi-original. There would be a lengthy bibliography, the production of which would give Lily a deep, almost rabid kind of pleasure.

But to actually sew?

She would never have spoken the wish aloud. Lily knows that she will struggle at sewing, just as she struggles at disconnecting tiny Lego pieces. But before she could take it back, Kyla had invited her and the other mother and some other women, too. Why not make it a party? she’d said. I’ll have wine, and snacks, and she will, Lily knows, because Kyla is always wearing boots with heels, even at the playground, and she sent real, paper invites to the thing: A Sewing Fête!

What does one wear to a Sewing Fête? Not baggy underwear, certainly. Not sweat.

Lily, smearing concealer under her eyes, spots a new gray hair in her left eyebrow, tweezes it, and feels instant remorse, not only for the hole she has made but for the pain. It’s enough to make her eyes smart with tears and to make June, whose shirt is off now but still in her hand, think that her mother is crying. She wipes her face with her shirt, as if demonstrating, then offers it to Lily, and Lily, who has again forgotten to stock the bathroom with tissues, accepts and wipes her eyes, remembering too late the concealer she just applied.

“Momma?”

But time! After a five-minute grace period, the school asks for a “donation” of a dollar a minute to cover care. It’s not required—the school is public, after all—but suggested, and the understanding is that you pay if you can, and Lily can in the sense that doing so will not make her homeless, and her daughter has the boots to prove it. So if she’s twenty minutes late? Fifteen dollars. Fifteen dollars is a cocktail shaken by a man in a vest, or overnight diapers for a month. It is a lot and not very much, though if you fail regularly in this way it becomes, undeniably, a lot.

“Momma!”

Ignoring June’s squeals, Lily carries her down the hall, throws her into the stroller and, with a knee between her legs, manages to strap her in, buckle the tiny, injurious buckles, and maneuver her out the door. June is shirtless and bootless but they make it, somehow, into the elevator, which causes Lily to remember that she was doing laundry in the basement earlier and that her wet sheets are still waiting in the washing machines—what will the super do with them this time?—but time is chugging along and look, she managed to grab a fresh shirt for June as well as the boots and also her own coat and hat and by the time the door opens in to the lobby they are, a miracle, ready. June smiles sweetly, and Lily pushes them out into the yellowing winter sunlight, and they join the river of other women and strollers and children on Eighth Avenue, heading to this school or that, or home from school, or to laundromats or piano lessons or nitpickers or playdates.

There are no men to be seen. It is 2016, four days into a new year. Lily breathes. The cold air wicks her sweat. The sky is blue, the bare trees make it appear bluer, the skin beneath her eyes appears smooth and bright. She will pick up her other child. She will go to the party. She will learn to sew.

Read along with us and join the conversation all month long on our Instagram account – GMA Book Club and #GMABookClub.