Angel of Harlem: How a patron saint to a forgotten generation of musicians came to face her greatest challenge yet

Wendy Oxenhorn was born the day blues harmonica great Little Walter died, and she said that a little part of her has always liked to believe that “maybe somehow I caught a molecule of his passing.”

Decades later, the longtime executive director of the Jazz Foundation of America (JFA) has left a mark on the world of American jazz and blues nearly as vivid and indelible as the glorious wail of Walter’s harp.

She landed alone in Manhattan at 14 to study with the New York City Ballet and trained with the famed dance troupe for years before an injury dashed that dream.

The day doctors told her she would never dance again, she called a suicide hotline and ended up counseling the counselor, whose husband had just left her. Three days later she joined the hotline staff.

In 1990, she co-founded Street News, the nation’s first homeless newspaper, which in its first year garnered a circulation of a quarter million, and inspired the creation of 150 similar homeless-generated newspapers around the world.

Oxenhorn managed to outfit her gritty, 2,000-strong sales team with free, branded canvas bags and uniforms that she secured by cold-calling and then sweet-talking then-president of the New York Times Lance Primis.

She spent a year in the subways, learning blues harmonica and busking with an old Mississippi bluesman, who helped sharpen her skills while she passed his hat.

The lithe blonde has lived a life too wild to fit inside even a song.

Her voice is warm and rich with imagery and soul and lines that sound like lyrics.

She describes a dreamy ex, hand clutched theatrically to her heart, as “oh my God, love like a blues song!”

Her bright green eyes beam as she breezily recounts the time in 1990 that she brought a homeless man on as a fellow guest on ABC’s “Regis & Kathie Lee.”

“He looked like James Dean, I’m telling you, and he was living on squirrel stew in Central Park.”

When she isn’t perfectly sure of something -- she’ll wink and assure you that “hell, it’s close enough for rock-n-roll, right?”

Yet now, Oxenhorn herself is facing a challenge more daunting than any of her work at the foundation. Over the course of several weeks of interviews by phone and in person, she ultimately decided that she is ready to reveal her own personal health issues. She said she’s okay with the troubling diagnosis she received privately a few years ago. Why shouldn't she be, she wonders aloud without prompting and looks you straight in the eye.

“I’ve lived my life like a run-on sentence with no commas.”

‘A Great Night in Harlem’

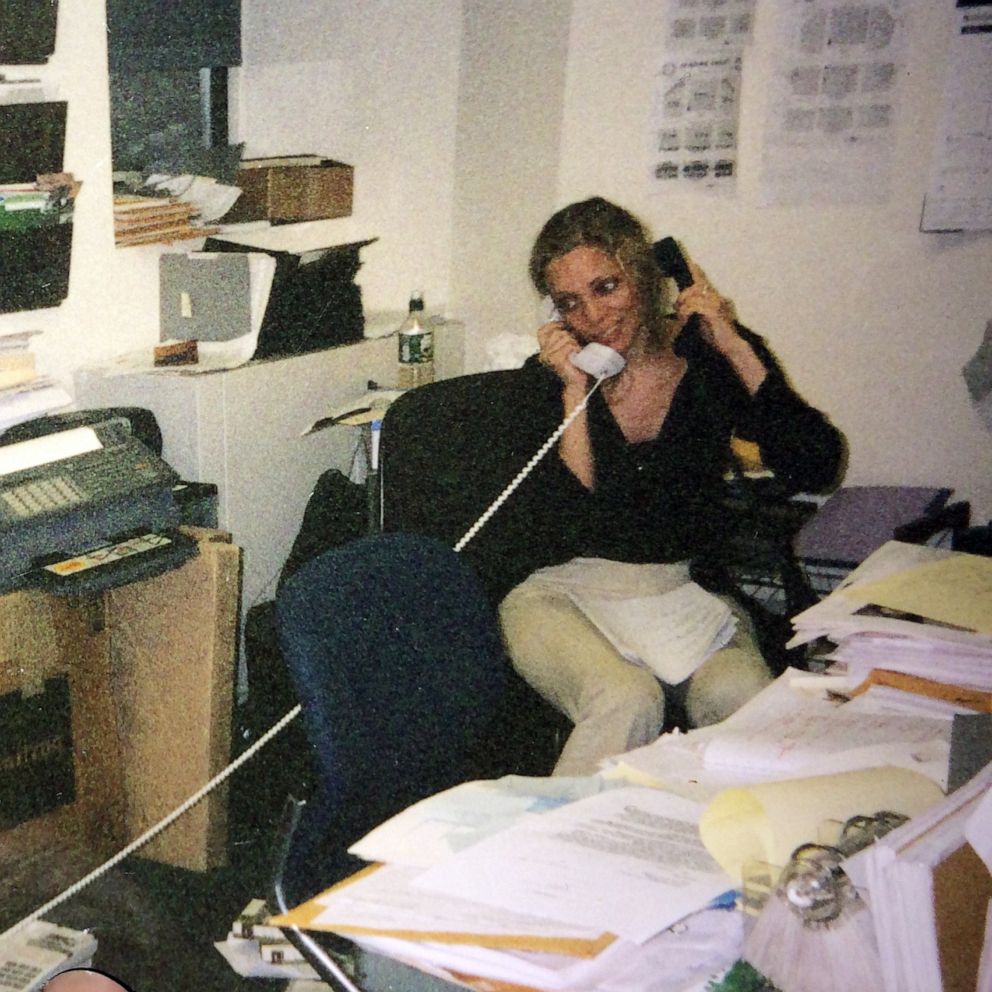

Oxenhorn was raising two kids as a single mom in New York City when she answered a newspaper ad in 2000 for a job at the non-profit JFA in Harlem.

The director was aging, the foundation was foundering and after a formal interview, Oxenhorn became the sole employee of the JFA.

She said she was stunned to learn the foundation had only $7,000 in its bank account, and set about dreaming up a game-changer. Since then, the foundation and its board of directors has grown in leaps and bounds to include supporters, donors and outreach staffers -- all working with Oxenhorn to expand the mission of the foundation.

"We are a family," Oxenhorn said.

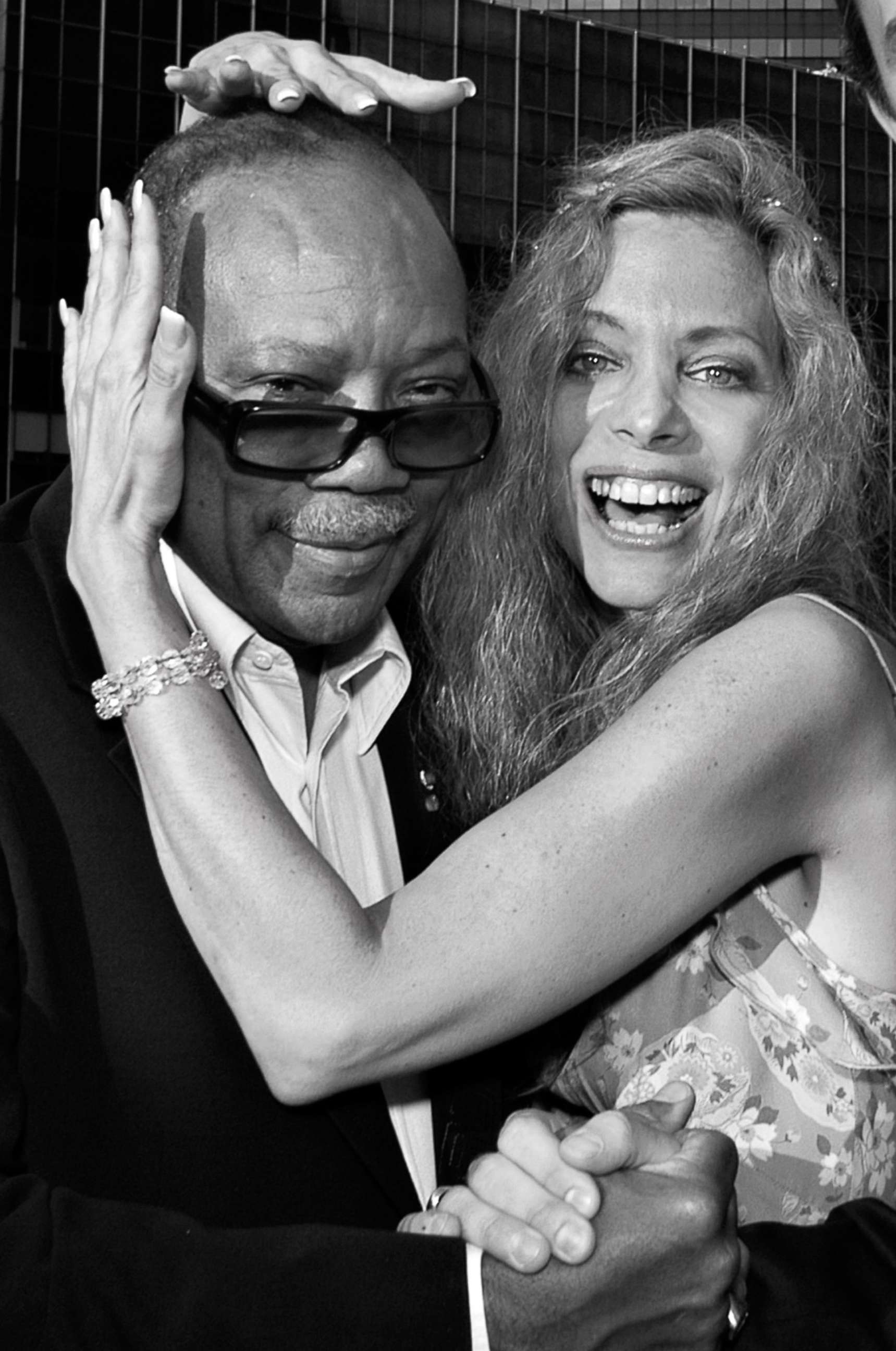

The following year, inspired by the iconic black-and-white Art Kane group photo of New York’s top-flight jazz and blues legends entitled “A Great Day in Harlem,” she conceived, pitched and launched “A Great Night in Harlem,” which has become a staple of the JFA’s annual fundraising drive.

Since that first trial run, the event has raised tens of millions of dollars for some of America’s most foundational musicians.

Recipients of JFA’s charity range from legends like Odetta, Roberta Flack and Jimmie Norman to lesser known pioneers like Sweet Georgia Brown and Johnnie Mae Dunson.

This week, Oxenhorn and the JFA will host some of the biggest names in jazz, blues, Hollywood, finance and philanthropy at the Apollo Theater in Harlem for the latest iteration of one the most-anticipated annual fundraisers in New York City -- headlined this year by Common.

“We all, in New York, get hit up to go to these galas and rubber chicken dinners and they’re all, you know, obligatory,” Dick Parsons, former chairman of Citigroup and former CEO of Time Warner, told ABC News.

I’ve lived my life like a run-on sentence with no commas.

“You wouldn’t call almost any of them fun,” he continued, frankly, “but the Jazz Foundation on the other hand? You want to go to their events.”

Parsons said he credits Oxenhorn for the spirit and energy of the annual fundraisers (a downtown “loft party” each fall has a similar reputation.)

“Wendy has what I call ‘peasant cunning.’ Such is her power and influence that, oh it’s got to be 12 or 13 years ago, when the former chairman of foundation passed away. And Wendy came to me and said ‘I need you to step in and do me and the foundation a favor -- and just be interim chairman until we can find the right person.’"

"So I said, ‘Sure, I’ll step in and do a few months, and I’m still the interim chairman.”

‘No place to turn’

Veteran rock drummer and bandleader Steve Jordan said that Oxenhorn is gifted with the ability to soften skeptical hearts.

“The people that the foundation helps are people that have a lot of pride and dignity and don’t want to ask for help," said Jordan, who with his wife Meegan Voss has been supporting the foundation and helping organize benefit shows for years. His extraordinary reputation in the business has helped draw music giants to the stage at the Apollo.

“This is the main thing that a lot of people don’t get about Wendy,” he said. “Whatever the situation is she has the ability to tap into helping people find relief.”

"Being a creative person or an artist -- it’s like a pre-existing condition: you can’t help wanting to continue to work and try to do as much as you can as a musician, [but] sometimes the cards are dealt in a way that that can’t happen, or you have to take a little break or all the sudden you can’t work. For most people there’s no place to turn in our field.”

Artist Elvis Costello, another JFA supporter, concurred.

“A lot of these people are literally living on their wits, or on the invention of their own music, their own talents,” Costello told ABC News. “It’s very difficult because people sometimes think people in music are very privileged. Well, a few are, but many, many more are not.”

“Down the years, there [have been] many of them working in very adverse circumstances, and against a background of all kinds of stories of prohibitions and prejudices and lack of respect. It goes right back into the debts of history, and the fact that somebody has the spirit to want to address some of these things?"

"It’s such a beautiful attitude that Wendy’s got," he continued. "Having somebody with a spirit like that is a wonderful thing in a world where, heaven knows, most people are out for themselves, you know?”

The late, legendary jazz scholar and Village Voice music critic Nat Hentoff described Oxenhorn in a 2003 column as “the most determined, resilient, and selfless person I have ever known.”

In 2016, at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C, Oxenhorn was honored by the National Endowment for the Arts with a Lifetime Achievement Jazz Masters award, and before that became the first American and the first woman to be invited to join the board of directors at the elite Montreux Jazz Festival.

‘Bodhisattva’

Actor Michael Imperioli, who got involved with the Jazz Foundation after being moved by the spirit of their work, believes that her role in the industry is thoroughly unique.

“I can encapsulate the thing that really inspires me about Wendy," he said. "When we did the loft party in the fall and she went up and gave an award to Sweet Georgia Brown...I’m looking at Sweet Georgia Brown, who’s very touched and very moved. But then I looked at Wendy and her face was just full with joy -- like the joy was just beaming out of Wendy’s face. It just broke my heart.”

“Because I said [to myself] ‘This is what this is about for her.’ She gets an immense amount of joy from helping people. I’m a Buddhist, [and] in my religion, we call that a bodhisattva -- someone who actually dedicates their lives to serving and helping others and that’s who she is."

“I’m surprised that she hasn’t been interviewed by Oprah Winfrey and lauded in some public way -- not to single out any one person, but she deserves to be on that sort of platform,” Imperioli told ABC News.

“People should really know this person," Imperioli said. "She should get a Congressional Medal of Honor as far as I’m concerned.”

'My heartbeat'

For her part, Sweet Georgia Brown called Oxenhorn “my heartbeat.”

After an apartment fire destroyed nearly everything she owned, the JFA got word and turned up.

“We’ve been together ever since,” Brown said. “Wendy has been my heartbeat.”

“She’s taken care of me, so I’ve gained a lot and I was so blessed to have them -- and Wendy and I get together all the time now. I love to cook and Wendy surprises me with shoes or clothes or pajamas or sexy things -- she keeps me pumped up, you know what I mean?”

Sassy as ever in the twilight of her career (“Write something good, Chris! Tell’em I’m still sexy at 72!”), Brown has been slowed down by a stroke she suffered last year, and has limited her regular gigs at a blues club in Greenwich Village. But her enthusiasm for the foundation was palpable during an interview last week.

“I’m 72,” she said. “I just had a birthday last week and they came and brought me a cake and champagne. I live in Hell’s Kitchen and I have a one-bedroom apartment the foundation got for me, looking over the city. I can see the Empire State Building. I can see all the tall buildings and the lights. I feel like I won the Lotto.”

I’m surprised that she hasn’t been interviewed by Oprah Winfrey and lauded in some public way -- not to single out any one person, but she deserves to be on that sort of platform.

Oxenhorn maintains an encyclopedic memory not just of her scores of musicians’ careers but their health problems, their bank statements and the names of their pets.

When she’s not working the room at her Wall Street fundraisers, or rehearsing with bands backstage at the Apollo, she’s out visiting her friends, as she describes them.

One day several years ago, down in Manhattan's East Village, Oxenhorn was sidestepping garbage in a housing project hallway to bring an impoverished old blues drummer -- who played in one of the most legendary jazz lineups in American music history -- a cake on his birthday.

She knocked on the door and whispered excitedly -- fan girl-like -- to me about all the legends he’s played with.

“He’s a-mazing,” she said.

Inside, as Oxenhorn leaned down to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to the elderly musician, with the late afternoon sun piercing a crack in the shades that illuminated him in the darkened apartment, the old man’s chapped, pursed lips slowly spread into a wide grin.

With the exception of Odetta, Norman and some of the other well-known recipients of JFA support, the foundation rarely identifies the musicians it helps, and only does so if the musician decides they want their identities publicized. The ones that do, handfuls among hundreds, say that they want their stories to illustrate the foundation’s work -- particularly Oxenhorn’s work.

The Jazz Foundation provides a range of support including medical care, money for housing and food and other vital services for older musicians, and in some cases, brief but thrilling returns to the glory of their youth.

In 2004, Oxenhorn arranged for Dunson to sing with Costello at a sold-out Apollo Theater benefit, and then rolled the wheelchair-bound 83-year old woman onto the stage to an explosion of applause.

Dunson was paid $5 a head in the 1950s to straighten musicians’ hair backstage before they performed -- and is now credited with penning hundreds of blues songs,that later found their way into the American blues lexicon, many of them sold to or stolen by more famous bluesmen like Willie Dixon, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed. She is said to have written the original versions of blues hits like "Evil" and "Wang Dang Doodle."

"When I first called her she was living in a state run [nursing home] in Chicago,'' Oxenhorn said. "She had no visitors and she didn't leave her room except in the middle of the night when no one would see her collecting aluminum cans."

The foundation got behind her. They began helping her with rent money, and re-introducing her to blues audiences from Chicago to New York City. In 2004, Dunson appeared at the Apollo Theater with Costello.

Oxenhorn vividly recalls the evening.

"You see this fragile, street-tough, savvy old girl, wheeled out in a wheelchair, and she takes this microphone in her hand and holds it like her life depended on it, and all of the sudden she starts singing, and the power that came out of her mouth brought people to their feet in seven seconds.'

"At one point, she got up out of her wheelchair, took two steps -- gave me a heart attack -- but she got up! This sound that was healing the audience was healing her!"

“And then,'' Oxenhorn said, her eyes wide with amazement, "when it was all over.... she'd been playing with Elvis Costello! -- she didn't even know who Elvis Costello was -- but she said, 'Man that boy can play some."

'Romeo and Juliet'

Jarrett Lilien, former CEO of eTrade and a longtime JFA board member widely credited with getting Manhattan’s finance industry behind the cause, said Oxenhorn’s determination is legendary in the music industry.

“One time at eTrade she wanted -- really wanted -- to talk to me about the Jazz Foundation and I just had no time and I had all these meetings and I then was going to be traveling,” Lilien recalled. “And then she said, ‘No, but I really need to talk to you,’ and I said, you know, ‘I’m going to be walking from one meeting on, like, 40th Street to another meeting on like 55th Street, so you’ve got like 15 minutes if you want to walk with me.”

“So, she met me and we’re walking and we passed two kids you know probably 18 or 19-years-old with a sign that said something like ‘Just married and stranded in New York’ or something. And we walked past them. And I could see how uncomfortable she was, but I had to get to my next meeting, so she kept walking with me, and we got to the end of the block and she just grabbed my arm and said, ‘look, I’m sorry, we’ll have to catch up some other time, I’ve got to go back.’”

“Those kids slept at her apartment that night," Lillian continued. "She got them a job at a restaurant through another person who’s a supporter of the Jazz Foundation and they earned enough….it was like Romeo and Juliet: their parents didn’t approve of them getting married so they eloped and came to New York and then were homeless and living on the street. And Wendy got them cleaned, got them some sleep at her apartment, let them work for a week or so so they got enough money to buy a ticket to go back to Ohio. That’s kind of Wendy in a nutshell.”

‘Their darkest hour’

Oxenhorn lights up when she recounts some of the most memorable connections that she and the foundation have made over the years.

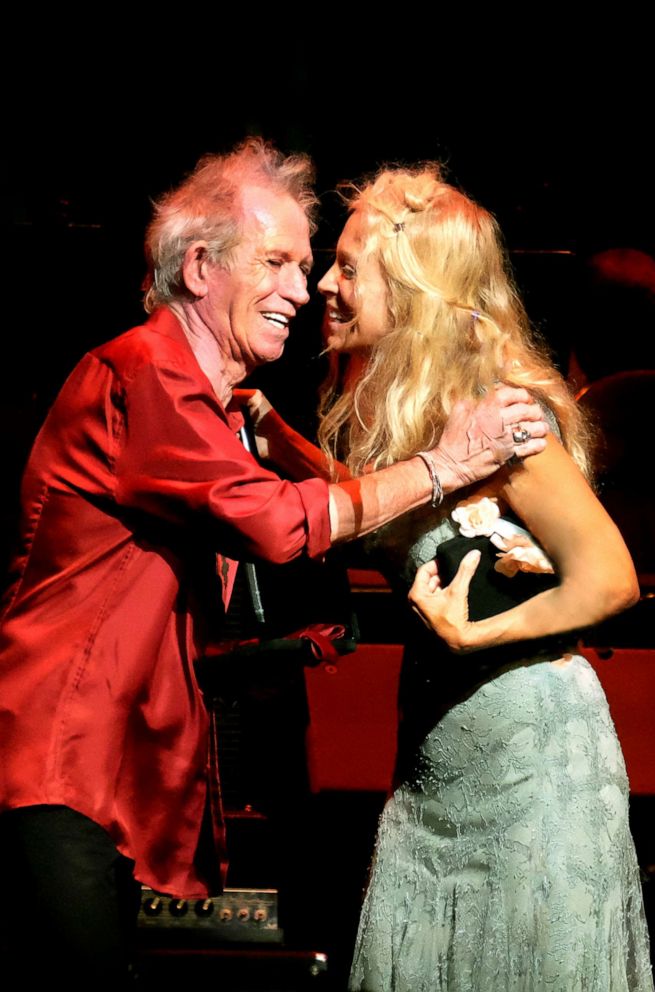

"These people spent their lives making music, and not making a dime," she told me in 2012. "I mean, Jimmy Norman, who co-wrote [the Rolling Stones' first hit] "Time Is On My Side," never got the publishing credits. He was one of The Coasters! He was one of Bob Marley's first producers."

"When we found Jimmy, he was ready to be evicted,'' Oxenhorn said. "He had emphysema so bad he couldn't sleep lying down, so he slept at night sitting up in a plastic chair,'' she said, growing visibly emotional. "His apartment hadn't been cleaned in years because of the heart condition."

"One of our volunteers found a tape from 1968 of him and Bob Marley writing songs in his apartment in the Bronx, songs that had never been heard before,'' she said. "It sold at Christie's for $20,000. He got himself a computer and some editing software, and he finally recorded his own version of "Time Is On My Side." His first CD! At 71 years old!"

"The people that you are helping are the people that were there for you your whole life - the people who literally played and wrote the soundtrack of your life,'' said Oxenhorn. "These were the people that [wrote the songs] for your wedding, and the ones that were there [on the radio] at 2 a.m. when you got divorced."

"It was Muddy Waters, or Odetta, or whomever, that got you through that girl in high school that broke your heart," Oxenhorn insists. "And now it's our turn to be there for them, in their darkest hour."

Jordan said that behind Oxenhorn’s child-like enthusiasm is years of saintly work among the most elderly and vulnerable musicians in the industry.

“She’s actually given almost two decades of her life to the foundation -- eating and sleeping the foundation and that is beyond commendable," he said. “It’s really extraordinary. Because what happens is when you work as hard as she has at trying to make people feel good, you start to kind of morph into the idea of the foundation itself. “

“So she is -- actually -- the foundation," Jordan insisted. "And it’s hard to separate one from the other. She tries to take some time off but she can’t because she’s always thinking about who she’s working with, or whenever she gets away she gets a call -- there’s always going to be somebody who has that super private number when they really need to talk to her. She’s never really off. She can’t do it. It’s really impossible for her because even if she wants to get away somebody finds her.”

‘Magical Simplicity’

Several years ago, Oxenhorn herself got some life-changing news: a birth defect had produced an extra collection of blood vessels in her brain stem, which had lived undetected in the back of her neck her entire life.

The blood vessels have grown worn and dilated and don’t belong there in the first place, she said that doctors had told her. If any one of the errant blood vessels pops, she was warned, she will likely die almost instantly.

“When you get kissed by angel of death, all you really know is the moment -- and you begin to live in the now, and all your worries about your kids and what’s going to happen to them? All the sudden it just goes, and you are left with this moment.”

These days Oxenhorn spends any downtime she can get in a trailer park on a breezy island off the southern coast of the U.S. Her brightly-colored, lovingly-ornamented trailer, which sits beside a rippling stream that winds through her tiny trailer courtyard, was gifted to her by a JFA donor. It’s the place where she said she rediscovers herself every time she returns -- a place of “magical simplicity.”

“So when you go to your tin palace on your little island and you choose to live in this wonderful simplicity -- this magical simplicity -- surrounded by plants and animals that remind us there is a oneness and we are all connected to each other -- that state of being is our true nature."

"Nature is free," she said. "Trees are free. Wild animals are free. We have to learn from them. They tell you everything," she insisted. "They are our teachers!”

She pauses for a beat to let the notion sink in -- for her and you both, it seems -- and then floats an even lighter thought.

“What’s so hilarious to me,” she concluded, looking back on a life of constant motion and endless charity, “is that what is going to kill me is stress – ‘physical and emotional stress are to be avoided at all costs,’ she said, mimicking her doctors’ admonitions.

‘But that’s just not me, you know?" she said. "I can’t live inside a bubble. I need to be out there dancing and in love with the world."

ABC News' Gerard Middleton contributed research to this report.