Public awareness of global warming is up and support for action is broad, with eight in 10 Americans saying the federal government should try to achieve the same deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions called for in the international treaty rejected by Donald Trump.

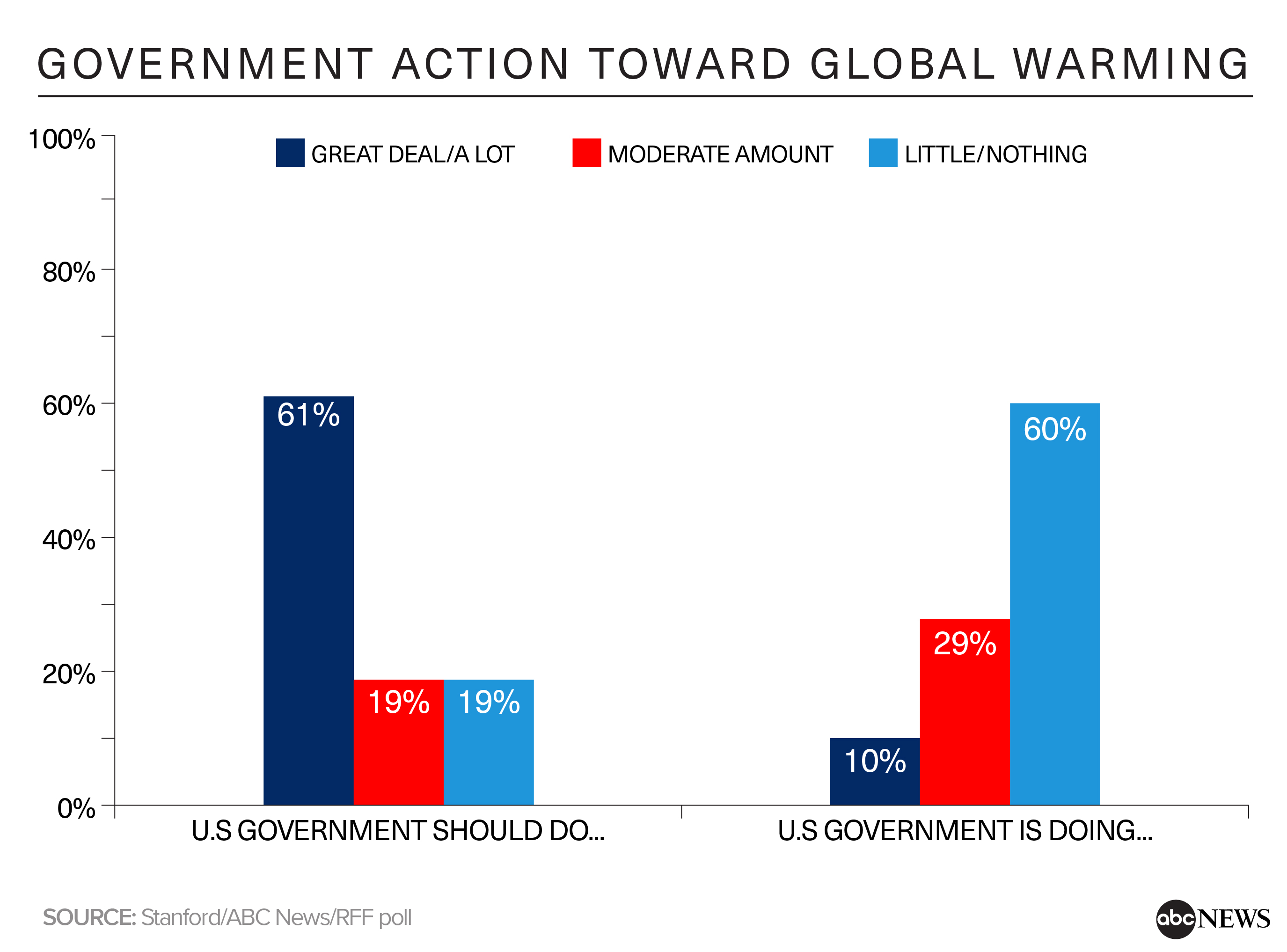

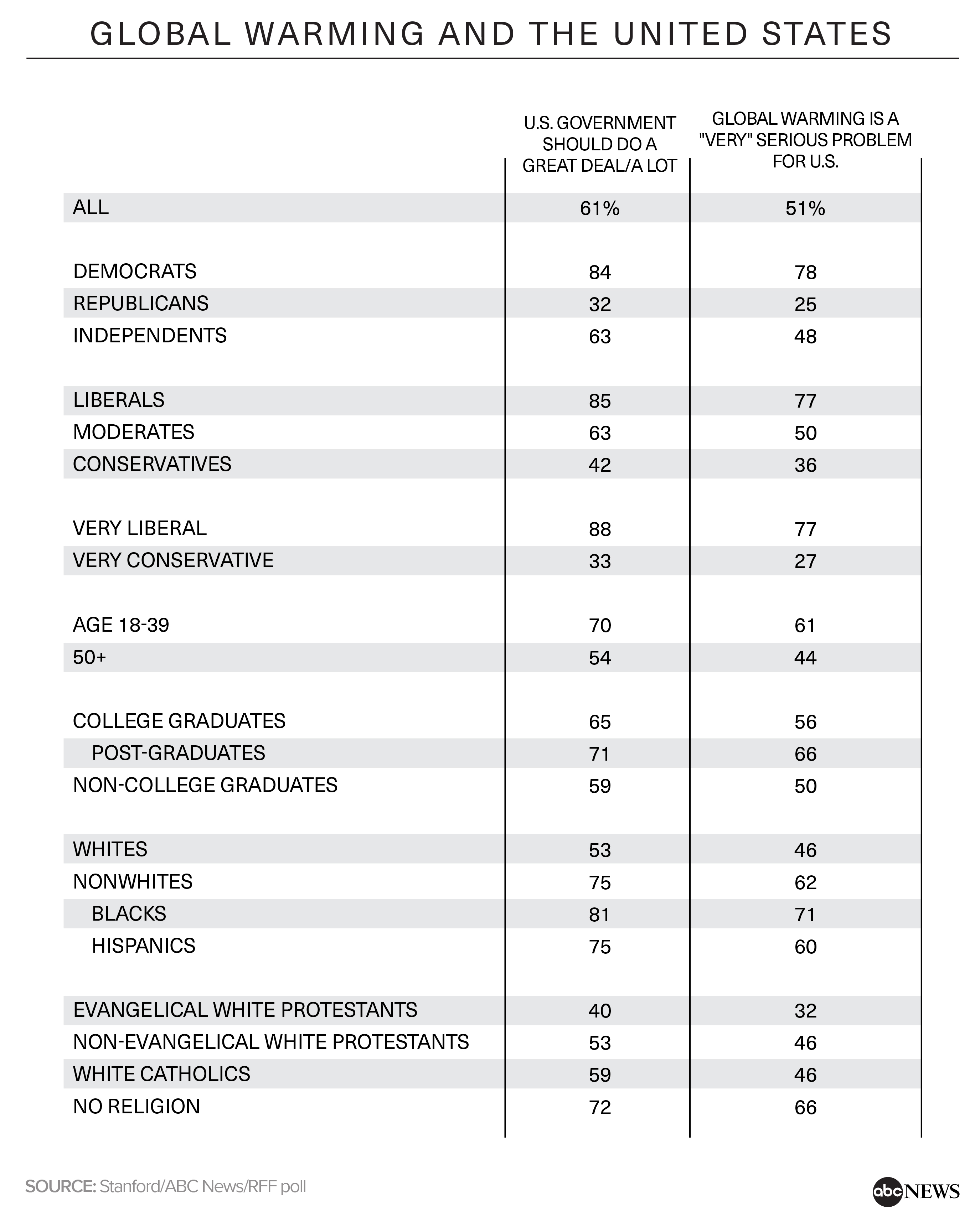

Sixty-one percent in a new national survey also say the federal government should be doing “a great deal” or “a lot” about global warming, up 8 points since 2015 to the most since 2009. A mere 10 percent say the government in fact is doing that much – down 5 points in three years.

See PDF for full results, charts and tables.

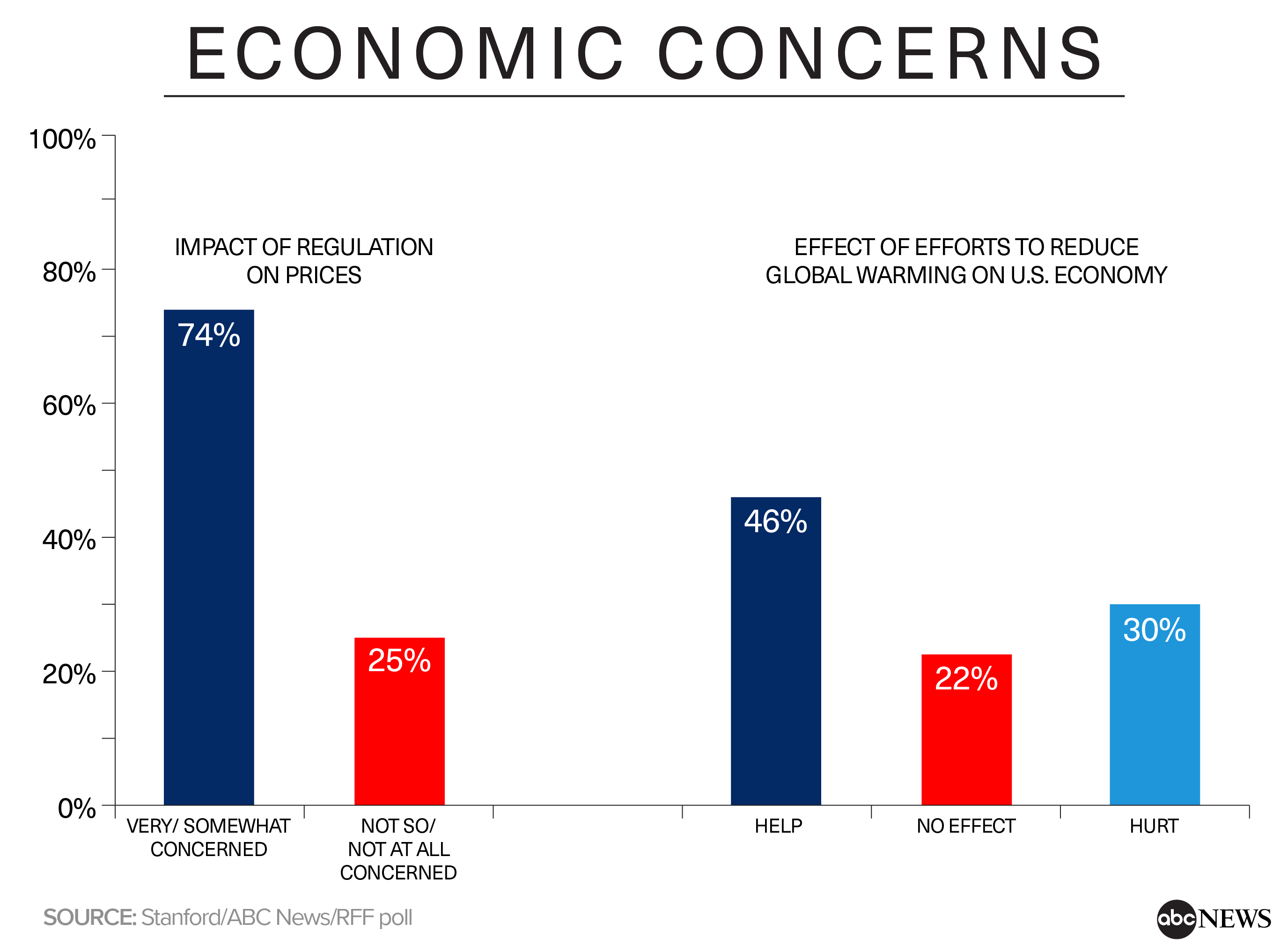

That said, three-quarters of Americans express concern that efforts to address the issue will raise prices on things they buy and just two in 10 are very confident that those efforts in fact would reduce global warming. The latter, in particular, contributes to an absence of broad urgency on the issue. Just a narrow majority, 53 percent, favors immediate action over more study. And many of those who back some policies think they should be voluntary, not mandated.

The random-sample survey was produced by ABC News, Stanford University's Political Psychology Research Group and Resources for the Future, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank focused on economic, environmental, energy and natural resource issues, with design, management and analysis for ABC by Langer Research Associates. It extends more than 20 years of research into attitudes on global warming by the Political Psychology Research Group at Stanford University — previously at Ohio State University — led by Prof. Jon Krosnick.

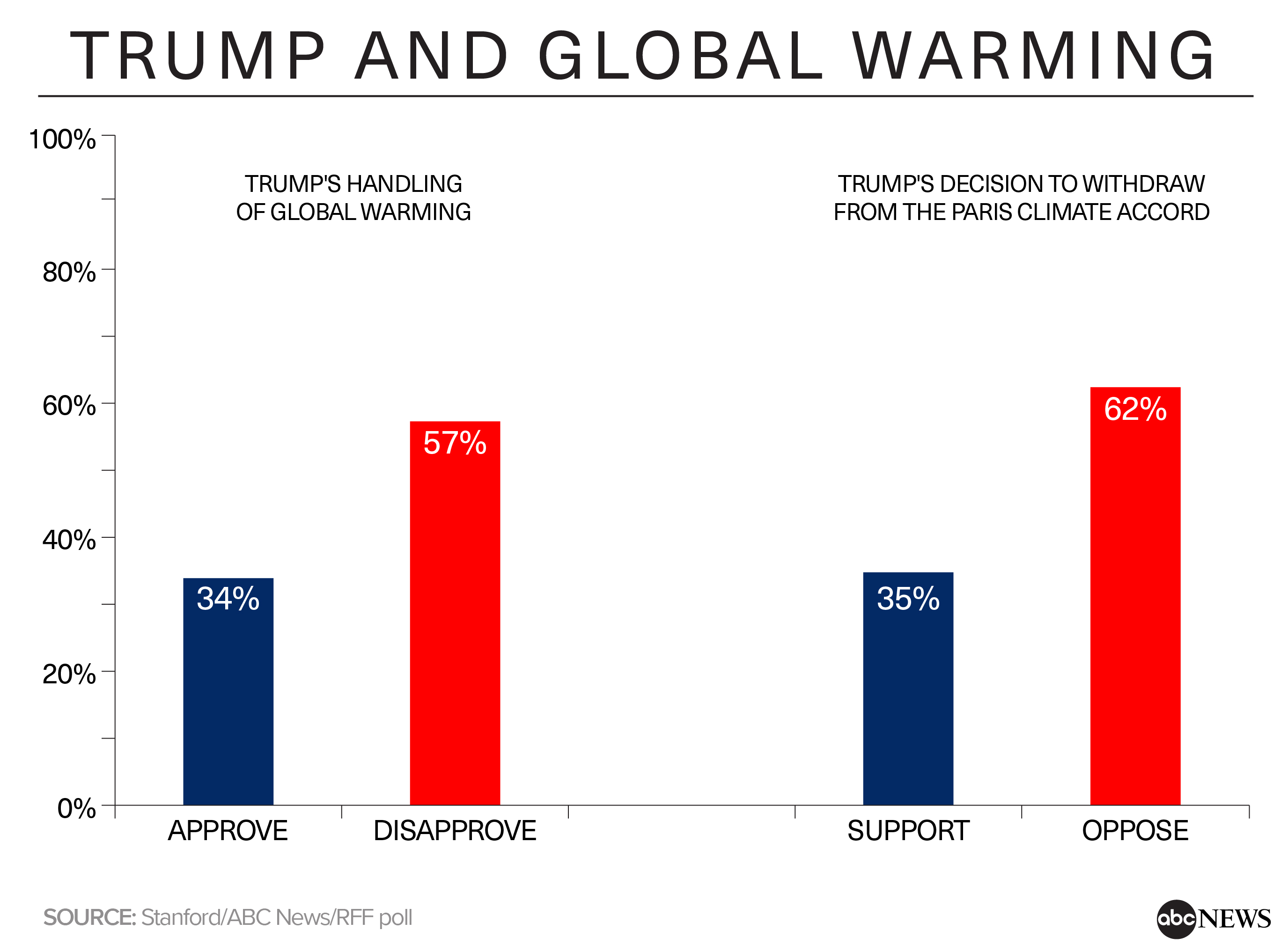

In the political realm, 57 percent disapprove of Trump’s handling of global warming overall and 62 percent oppose his planned withdrawal from the Paris climate accord. Strength of sentiment is broadly against him: Just 19 percent strongly approve of his handling of global warming, while 44 percent strongly disapprove. On the climate treaty, he has 23 percent strong support for his position, vs. 48 percent strongly opposed.

It’s unclear how much weight the issue of global warming may carry in the November elections. Fourteen percent of registered voters both support robust government action and call the issue extremely important in their choice of candidates – enough to matter, especially in a close contest. That said, just 8 percent in this group are Republicans; 65 percent are Democrats (and 57 percent are liberals), and the remaining independents lean Democratic by a wide margin. As such, the GOP’s exposure among its customary supporters looks quite limited.

That said, 48 percent call the issue highly important to them more generally, up 6 points from 2015 and 5 points above the average since 1997. Twenty percent call it extremely important, a new high.

Overview

Among additional findings from the wide-ranging survey:

• Seventy-two percent of Americans feel they know a great deal or a moderate amount about global warming, up 6 points from 2015 to the most in Stanford surveys since 1997. Self-reported awareness has grown from 43 to 72 percent across this 21-year period.

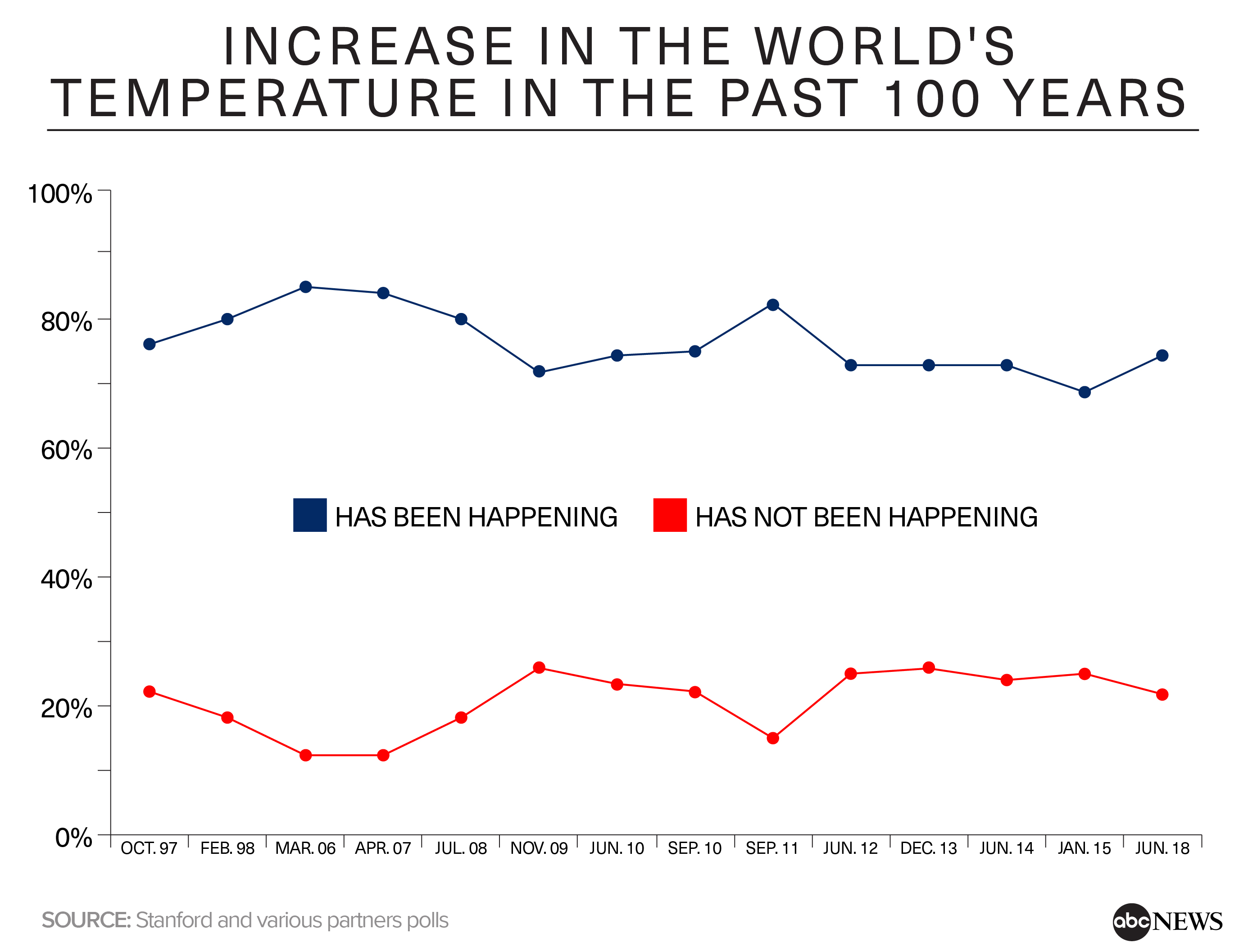

• Seventy-four percent say global temperatures have been rising in the past 100 years, matching the 21-year average. (This is up 5 points from 2015, but off its peak, 85 percent in 2006.) Eighty-one percent think this either is mostly because of human activities, or about equally because of human and natural causes, dividing about evenly between the two.

• While 57 percent are confident that government action would in fact reduce global warming, just 19 percent are very confident of this. And while 70 percent of those who are not registered to vote are confident, this falls to 53 percent of registered voters. As noted, confidence in solutions can be a precursor to motivation to act.

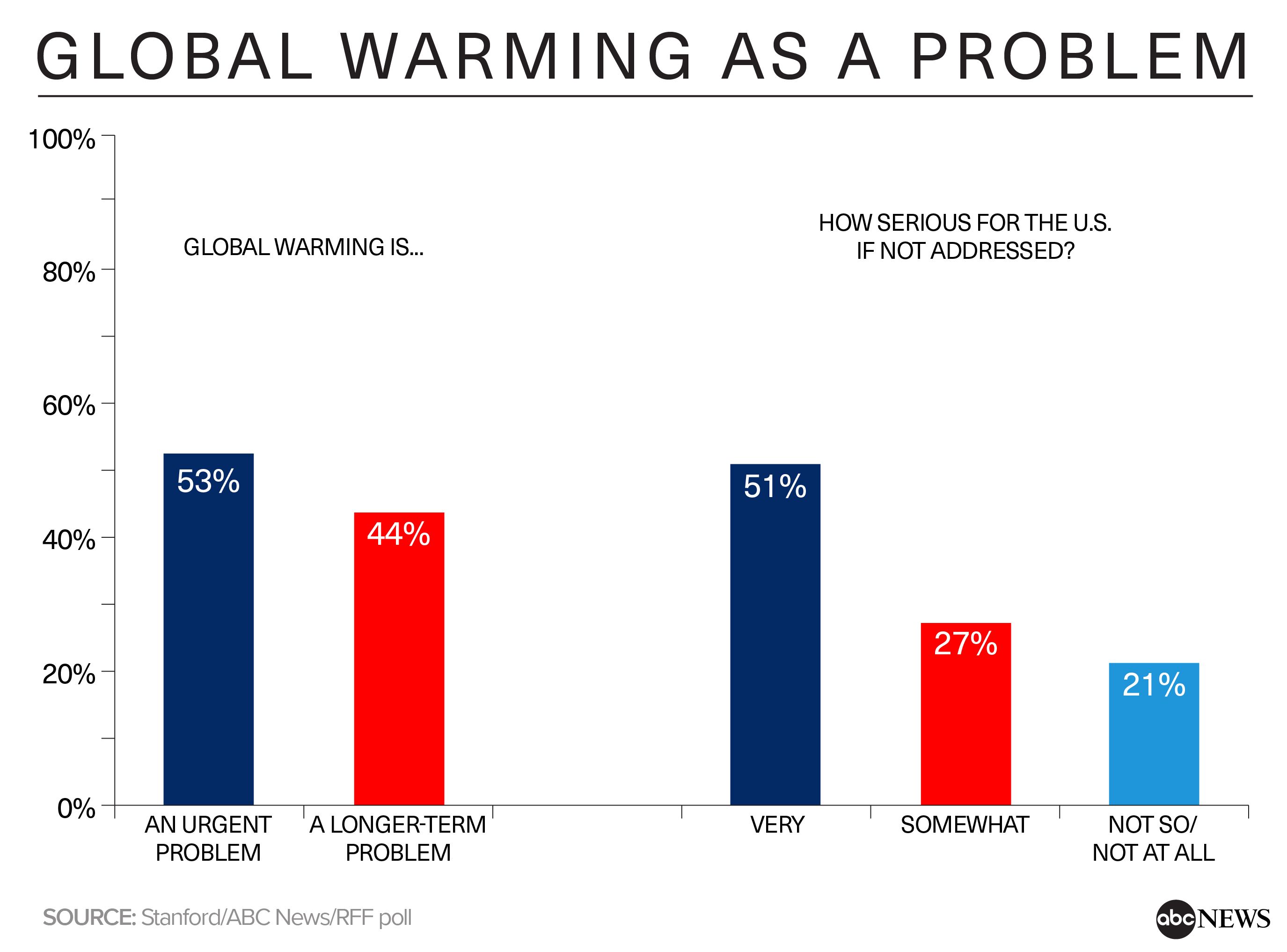

Further, while 53 percent call global warming an “urgent problem that requires immediate government action,” that leaves 44 percent who instead call it a longer-term problem requiring further study first. And just a bare majority, 51 percent, foresees a very serious problem to the United States if nothing is done to reduce global warming in the future, although that’s 5 points more than the average in eight surveys since 2006.

• Criticism of the oil industry is widespread: Seventy-nine percent think major oil companies engaged in a cover-up of their products’ role in global warming, with broad majority agreement across partisan and ideological lines, a relative rarity. Far fewer, meanwhile, think climate scientists have exaggerated the problem – 30 percent overall, but, in a return to form, soaring to 68 percent among strong conservatives.

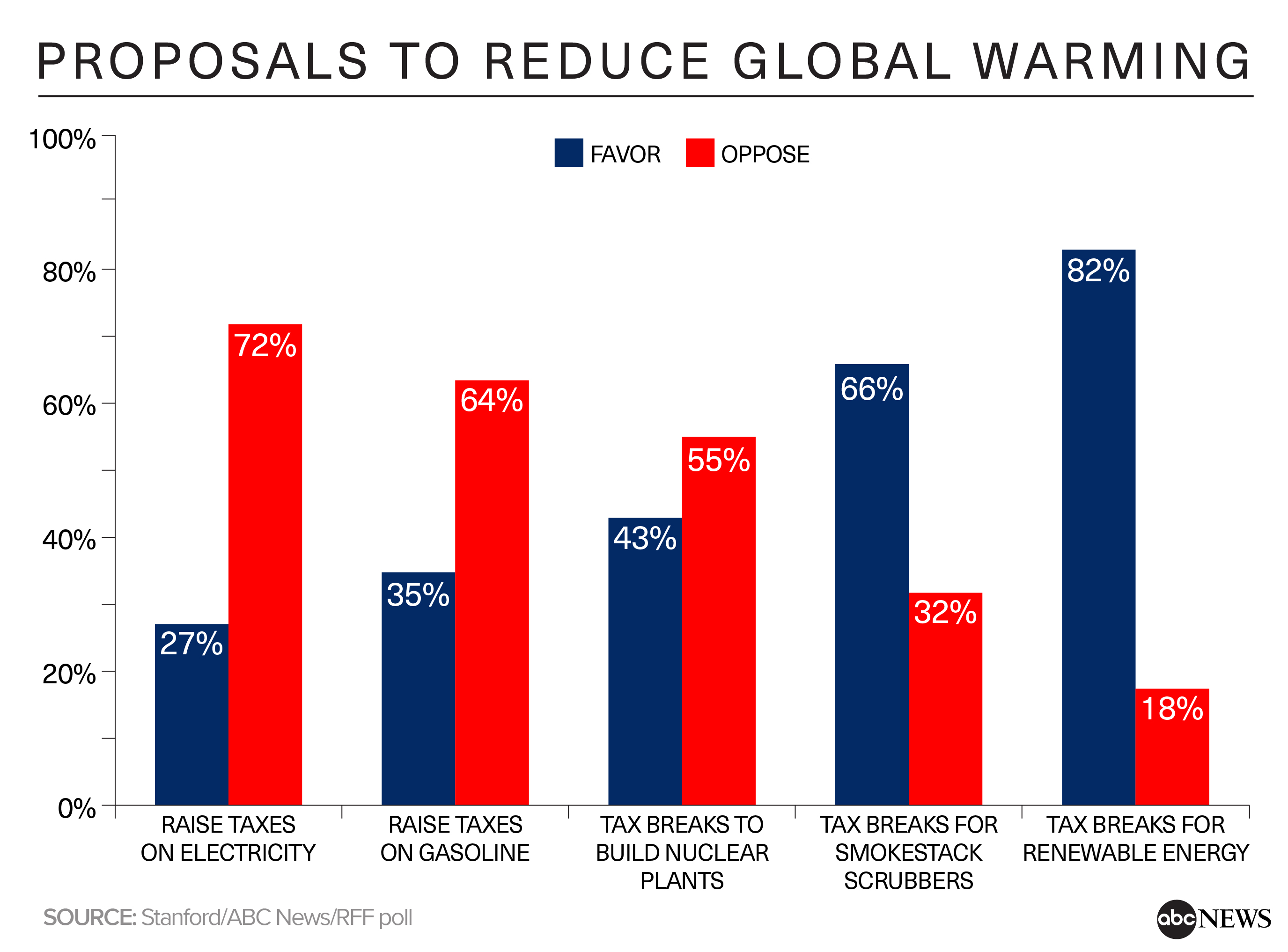

• Taxes that raise electricity or gas prices to try to decrease consumption are not popular, and 74 percent express concern about the impact of climate change regulation on the prices they pay for things generally. Even among Democrats and liberals, six in 10 oppose higher taxes on electricity.

Business- rather than consumer-focused actions earn more support. Seventy-eight percent say the government should limit the amount of greenhouse gases that companies put out. (It was similar, 81 percent, in 2013.) Sixty-eight percent favor taxing companies based on their release of greenhouse gases, and if the fuel is imported from other countries, support rises to 78 percent. These are up 7 and 11 points, respectively, compared with similar questions asked in 2015, in a survey by The New York Times, Stanford and RFF.

• Trump’s support for the oil and coal industries does not reflect the public’s priorities. Americans by 70-21 percent say the better way for the government to encourage job creation is by developing the renewable energy industry rather than by protecting the traditional energy industry. Fifty-three percent strongly favor backing renewables, vs. just 12 percent who strongly favor focusing on traditional energy.

In current news, demonstrators, particularly young people, are expected in Washington next Saturday in a march supporting action on global warming. The survey confirms some differences among age groups. At the most basic level, 81 percent of 18- to 39-year-olds say global temperatures have risen in the past century, vs. 68 percent of those 50 and older.

Support for substantial government action ranges from 70 percent of those 18-39 to 54 percent of those 50-plus. Young people also are much more confident in such action, 71 vs. 48 percent; and more apt to see serious risks to the United States if it’s not taken, 61 vs. 44 percent.

Partisans

Chiefly, though, wide partisan and ideological differences mark many public attitudes on global warming, as is typical. In one important example, high levels of trust in what scientists say about the environment – a key predictor of other global warming attitudes – ranges from 58 percent among Democrats to just 32 percent of independents and 22 percent of Republicans. At the most extreme, 74 percent of strongly liberal Americans express this level of trust in environmental scientists, while a mere 6 percent of strong conservatives agree.

Such divisions cross the spectrum from policy preferences even to observations about climate and weather patterns. Democrats and liberals are 32 percentage points more apt than Republicans and conservatives to say the world’s temperature has risen in the last 100 years. Liberals are 37 points more apt than conservatives to say global weather patterns have become more unstable and 34 points more likely to see global warming as chiefly human-caused. Eighty-four percent of Democrats and 85 percent of liberals back robust government action on global warming; 32 and 42 percent of Republicans and conservatives agree, in part because they’re vastly less likely to think it will work.

That said, there are cases of greater commonality. On one hand, few in any group are very confident that government action to reduce global warming will have the desired effect; 25 percent of Democrats think so, for example, as do 14 percent of Republicans.

On the other, there’s general support in some cases for trying. Substantial majorities of Republicans (70 percent) and conservatives (66 percent), for example, say the country still should try to achieve the 25 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 levels envisioned in the Paris climate change treaty, despite Trump’s action to withdraw. Support rises to more than eight in 10 independents and moderates and more than nine in 10 Democrats and liberals.

While partisanship and ideology are the heavyweights, there are differences in global warming attitudes among other groups. In addition to age, education, race and religious belief are differentiators. Concern and support for action is particularly high among the 12 percent of Americans who’ve obtained a postgraduate education; among nonwhites as opposed to whites; and among those who profess no religion, while notably low among evangelical white Protestants. Like age, however, these largely reflect the partisan or ideological composition of these groups.

In statistical modeling, higher trust in scientists is a strong predictor in thinking both that global warming is happening and that it’s a serious problem for the United States. Perceived instability in global and local weather patterns also are positive predictors, while being or leaning Republican, conservativism, age and income are negative predictors.

Specific Actions

In policy terms, one result underscores the longstanding appeal of energy produced from water, wind and sunlight. Out of a list of five possible government actions, giving tax breaks to companies to produce more electricity from renewable sources is most popular by far, favored by 82 percent – another item on which partisan and ideological divisions subside.

Two-thirds also favor tax breaks for coal-fired power plants to install smokestack scrubbers. Forty-three percent back tax breaks to build nuclear power plants – up 7 points from 2015, albeit below its peak, 54 percent, in 2009. Fewer endorse taxes that would directly impact consumers, either on gasoline (favored by 35 percent) or electricity (27 percent).

Another question asks if the federal government should require, encourage or stay out of several policy options. Topping the list, 51 percent say it should require power plants to cut their output greenhouse gases. An additional 32 percent say this should be encouraged but not required.

The go-it-alone approach taken by some states, particularly after Trump’s announcement on the Paris accord, is not the preferred path; 59 percent say states should follow the federal government’s rules on greenhouse gases, not make their own. That said, as noted, the number who say the federal government should be taking extensive action exceeds the number who say it’s currently doing so by 51 percentage points, a vast margin.

Compunctions

Potential economic impacts are a concern. Even as 78 percent of Americans say the federal government should limit greenhouse gas emissions, nearly as many, 74 percent, say they’re very or somewhat concerned that such regulation could substantially raise the prices they pay for things. Thirty-five percent are very concerned about it.

At the same time, more think government action on global warming will help the economy than think it will hurt it, 46 vs. 30 percent, with the rest expecting no economic impact.

As often is the case, many also express less-than-supreme confidence that government action will produce the desired results. As noted, 57 percent are very or somewhat confident in such action. That leaves four in 10 who lack confidence that government steps to reduce global warming will work. Among them, only 29 percent say global warming needs to be addressed immediately, compared with 70 percent among those more confident in government efforts.

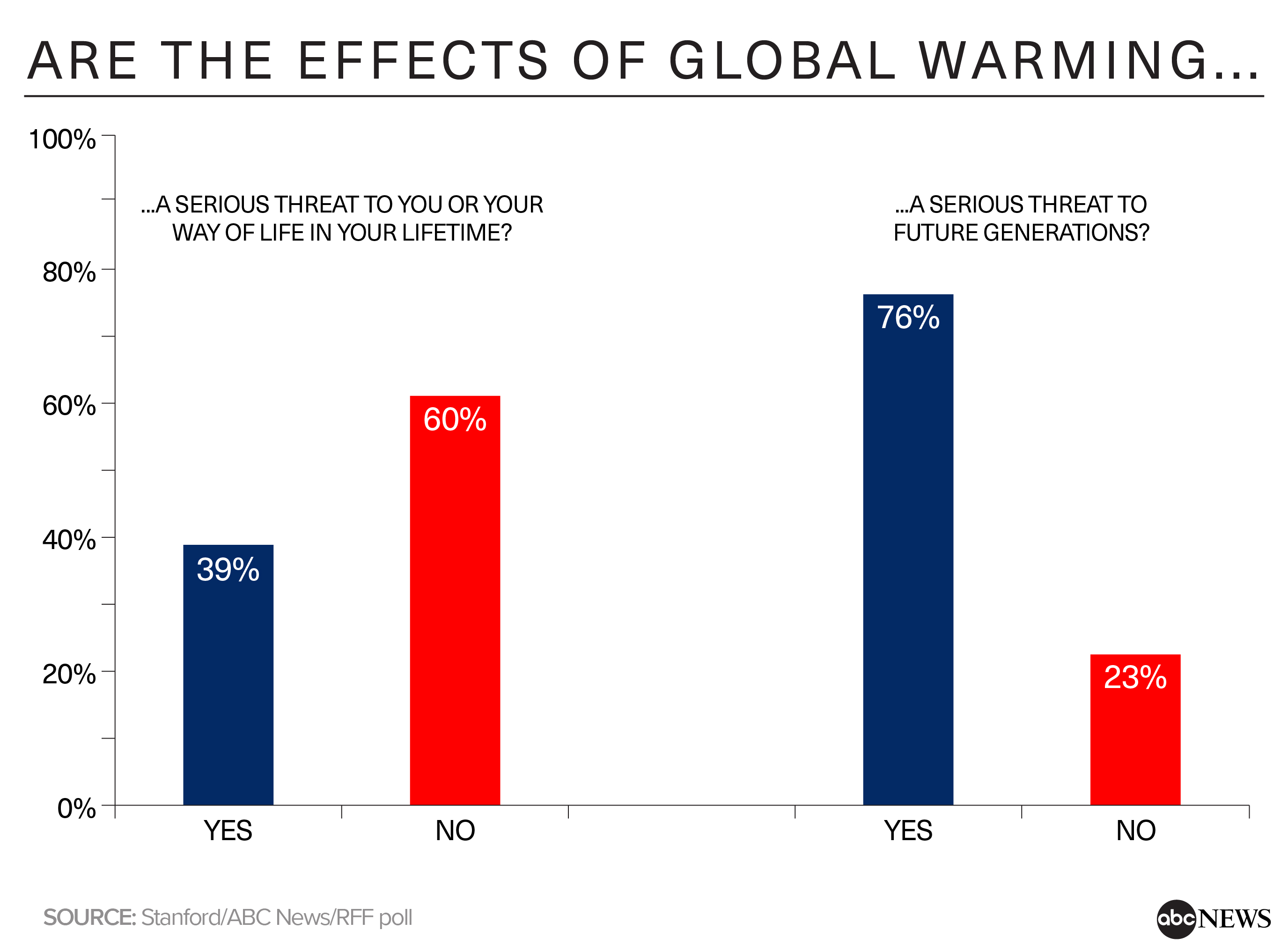

Seventy-nine percent foresee a serious problem for the United States if nothing is done to prevent global warming in the future and 76 percent see a serious threat to future generations. But fewer, 51 percent, see a “very” serious problem to the country, and fewer still, 39 percent, think the effects of global warming pose a serious threat to their own way of life in their lifetime.

These views matter. Eighty-one percent of those who see global warming as a very serious problem for the country believe it requires immediate action; that falls, dramatically, to 33 percent of those who say it’s “somewhat” serious, and into the single digits beyond that.

Those who don’t see lifestyle impacts on the horizon for themselves or future generations also are less likely to say action is needed now. Among those who don’t think global warming will threaten their own way of life, 36 percent say it’s an urgent problem, compared with 77 percent of those who think it will. More starkly, in the smaller group that doesn’t see a threat for future generations, a mere 6 percent back immediate action, compared with 66 percent among the three-quarters of Americans who do see such a threat.

Further, among those who think the world’s temperature has been rising, just 29 percent are “extremely” sure about it – though this is a new high, and 59 percent are extremely or very sure. Among those who think global warming has not been happening, far fewer, 36 percent, are that sure of their position.

Overall, nine in 10 of those who say global warming is extremely or very important to them strongly support government action, vs. just 13 percent of those who say it’s not too or not at all important. In statistical modeling, this result strongly predicts support for government action, as do seeing global warming as a threat to future generations, confidence in government action, thinking that action would help the economy and trust in what scientists say about the environment.

Other Results

Among other findings, the survey shows a persistent underestimate by the public of Americans’ acceptance of the idea that the world’s temperature has been rising over the past 100 years. On average, Americans estimate that 57 percent of the public thinks temperatures have been rising, while in fact, as noted, 74 percent think this is the case.

There also are a few conflicts in the results. Fifty-six percent say the government should require that cars and light trucks manufactured after 2025 get 55 miles per gallon, an Obama-era regulation that the Trump administration is reconsidering. But in a different question, just 24 percent say manufacturing cars that use less gas should be required – a single point from the low, and down from 45 percent in 2006. An additional 45 percent say this should be encouraged but not required.

In another example, as covered above, 78 percent say the government should limit greenhouse gas emissions by businesses, but many fewer in another question, 51 percent, say the government should require a reduction in such emissions from power plants, (An additional 32 percent say these cuts should be encouraged.) And there’s a 20-point gap between those who favor trying to achieve a 25 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions, 81 percent, and those who want the government to do a great deal or quite a lot to address global warming, 61 percent.

The conclusion is that competing interests are at play. Recognition of global warming and concern about its long-term impacts are broad, if highly partisan. Solutions are widely desired, especially when problems or remedies are clearly identified. But a somewhat skeptical public, concerned about costs, resistant to mandates and uncertain that proposed solutions will work, harbors continued doubts about how best to pursue them.

Methodology

This ABC News/Stanford/Resources for the Future poll was conducted by landline and cellular telephone May 7-June 11, 2018, in English and Spanish, among a random national sample of 1,000 adults. Results have a margin of sampling error of 3.5 points, including the design effect. Partisan divisions are 30-23-35 percent, Democrats-Republicans-independents.

The survey was produced for ABC News by Langer Research Associates of New York, N.Y., with data collection by ReconMR of Austin, Texas.