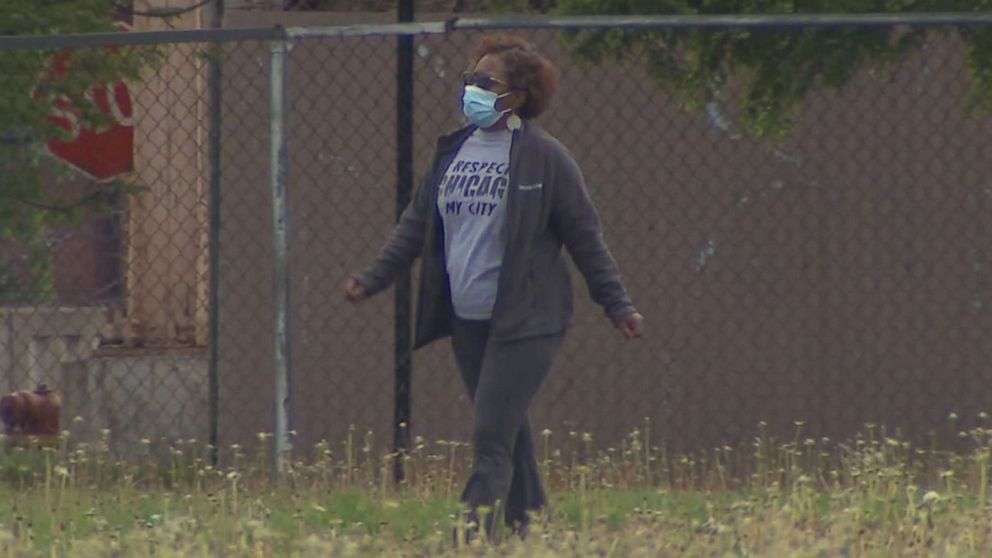

Jackie Gordon walks the same Chicago track every day, circle after circle, alone.

“So much happens to us that nothing really surprises you anymore,” Gordon told ABC News correspondent Deborah Roberts.

Alone and neglected is how many in Chicago’s Auburn Gresham community have felt for years, stuck in a circle of poverty that existed long before this pandemic.

Tune in for the full report at 7pm & 9pm EST on ABC News Prime available on multiple platforms... Hulu, Roku, YouTube TV, Apple TV, Xumo, Sling TV, Facebook, Twitter, ABCNews.com, and the ABC News and ABC mobile apps.

Nakiea Love has lived here her entire life. “In this area we don’t have a lot of the resources that we need to have, whether it is dealing with food or dealing with health, just the everyday things that people need, the necessities we have to have,” she told ABC News.

In the 1940’s Love’s grandparents helped integrate the block, a community that is now 96 percent black. “Everyone is so close-knit because we’ve all just been here for so long,” Love said.

Auburn Gresham is considered ground zero by many for COVID-19 in Chicago and the state of Illinois. This community saw the first COVID-19 death in the state, more than two months ago. But this is certainly not the first time it has dealt with adversity. Residents here say businesses were closing, including the supermarkets many relied on to get fresh food.

According to the latest available neighborhood data, unemployment in Auburn Gresham was approaching 30%. That’s before an estimated one in four Americans lost their jobs during the pandemic.

Nakiea Love is one of those Americans, and she says being furloughed has sent shock waves through her family.

“It is challenging... the first thing that went into my mind was, How am I getting ready to feed my child every day, all day?” Love said.

She is not alone.

Food insecurity is on the rise not just in Chicago but in cities and states across the country.

(MORE:As coronavirus continues, so does food insecurity)Since the pandemic began, according to the Brookings Institution, 17 percent of moms with children 12 and under say their kids are not eating enough because they can’t afford food.

That’s a 460% increase from 2018.

“In my community in Detroit urban areas there is not a lot of opportunity to have really healthy food, I’m going to be really clear and honest with you,” Shardaya Fuquay told ABC News.

The latest USDA numbers from before the pandemic found roughly 11% of Americans are food-insecure.

Tulane professor Diego Rose would not be surprised if that number surges past 15% when new data comes in.

The USDA says spending on SNAP benefits has increased 40% during the COVID-19 emergency. In April, SNAP households received $6.5 billion, up from the typical $4.5 billion.

It’s taken a virtual village to help parents like Fuquay, “I can’t think about creative activities because I’m thinking about, I’m about to get evicted, I know I need to feed you today,” she said.

She was among the 200 families offered a $500 grant by the Detroit charity Focus Hope.

The grant money helped families with essentials and missed bills, money that likely wouldn’t have arrived this quickly if not for a network of black donors with means.

“What we really understand is that as a community we have to take care of ourselves, we can’t rely on anyone else to take care of ourselves,” BET President Scott Mills told ABC News.

Mills recognized how the virus was hitting communities of color early on and sprang into action.

“While the country was focused on how this was going to impact the country at large, we were very specifically focused on, Holy cow, the effect of this on the African American community is going to be uniquely devastating because it’s going to compound these preexisting conditions,” Mills said.

Pre-existing conditions like food insecurity.

While the daily struggles among African Americans are real, there are those in the top tier -- CEOs, business executives, others -- who want to give back. An Urban Institute study found that of any race, black families contributed the largest proportion of their wealth to charities.

In just a matter of weeks, Mills recruited an eager group of anonymous donors of color who exceeded his expectations in getting blacks across every industry to step up. He raised $17 million.

That money has been dispatched all across the country, pouring into charities in Los Angeles, Atlanta, New Orleans, New York, Detroit — charities like the Greater Auburn Development Corporation in Chicago.

Responding to the needs of its community, the charity has completely changed how it has operated in just a matter of weeks, now focusing exclusively on COVID-19 emergency response, from rent assistance to wellness checks to food distribution. Just last week it started a pop-up food pantry and on Monday, more than two months after that first COVID-19 death, it opened the first community testing site.

Improving public health in this community has been something this charity has been trying to do for years; long before the pandemic, they had been trying to get the funds to open a health center. The building they purchased still sits vacant on 79th street, in the heart of Auburn Gresham.

The organization's CEO, Carlos Nelson, told ABC News, “If we had been able to stand this up, who knows how many families we might have helped,” he said. “Where do we go from here? Because as soon as this ends, we’re still in the same predicament.”

It's a circle of poverty those who are able are desperately trying to break.

“If there’s something positive that we can extract from this, it is this call to arms to address the structural deficiencies and the structural barriers that are impacting our community. Because something will happen again; this is not the end. And we really have to make sure that our community is better positioned to prosper in good times, and to not suffer disproportionately in difficult times,” Mills said.

Sitting isolated at home with her 12-year-old daughter, Nakiea Love says she’s not surprised to learn a lot of people of color who are privileged are stepping up to help.

“We are very intelligent people.... I’m grateful to hear that.... It actually encourages me more to keep going, one day I will be on the other side helping the next person giving back to my community,” Love said.